This piece was written before the fall of the Syrian Arab Republic and the capture of Damascus earlier this month. Given the collapse of the last Ba’athist government, it seems even more appropriate to review the origins and history of an ideology that once inspired intense support and hope, which has since been replaced with battle-scarred landscapes. This is also available as a documentary episode.

For several centuries, much of the Arab world was dominated by the Ottoman Empire. However, over the course of its slow decline but especially with its defeat in the First World War and its subsequent collapse, the Ottoman Middle East was replaced by newly established Arab states. Promises by Western powers during the war were quickly broken as the British and the French carved up the region for themselves as a result of the Sykes-Picot Agreement. The resulting borders disregarded local realities, splitting up ethnic groups, tribes, and other communities on the basis of what was in the interest of London and Paris.

As a result, anti-colonial and anti-imperial sentiments grew significantly. A desire for a rebirth or a renaissance, ba’ath in Arabic, became widespread. Ba’athism was one of a plethora of left-leaning pan-Arab nationalist movements and ideologies that ascended into power following the end of the Second World War, which had left European imperial powers considerably weakened. Ideologically similar albeit separate phenomena emerged in Nasser’s Egypt and Gaddafi’s Libya. All of them, including Ba’athism, advocated the unification of Arab states into a single Arab nation. Ba’athism differed, however, in that it was a party-based ideology though it would become increasingly personalised in both Iraq and Syria.

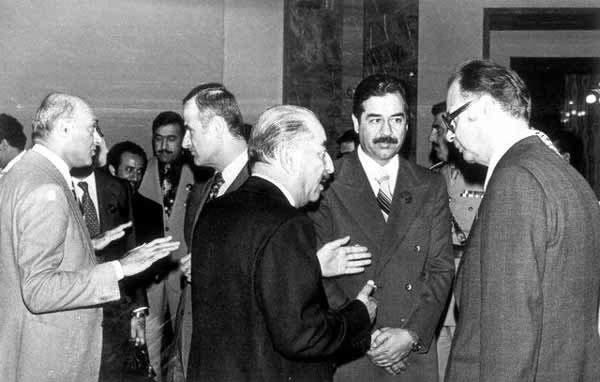

Despite advocating a unification of the regionally dominant ethnolinguistic group, it would prove to be popular among many minorities. In Iraq this was most notably the case with Sunni Arabs while in Syria it would be Alawites (adherents to a Shiite sect), with Christians in both countries also supporting the party in significant numbers. One prominent example was Tariq Aziz, a Chaldean Catholic born with the name Mikhail Yahunna who would later go on to be a long-serving Iraqi foreign minister and deputy prime minister.

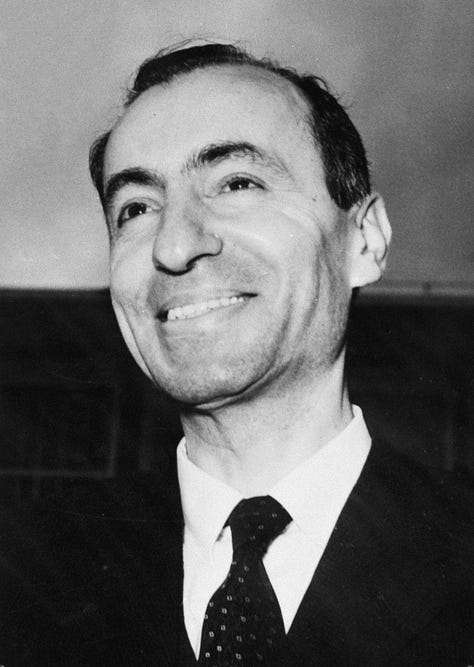

After all, the party was founded by three Syrians that consisted of Greek Orthodox Michel Aflaq, Sunni Arab Salah al‐Din Bitar, and Alawi Zaki al‐Arsuzi.

Despite its ostensibly broad appeal, Ba’athism was not universally supported. Though it had some among its ranks, the party struggled to attract Kurds, who were more predisposed towards Kurdish nationalist groups and were subsequently repressed in a bid to strengthen the Arab identities of the Ba’athist states. In addition, numerically larger groups who found themselves marginalised by politically dominant minorities would increasingly come to resent the Ba’ath Party’s hegemonic rules. Consequently, in Syria it was often Sunni Arabs who led anti-Ba’athist movements while in Iraq, where the Sunni Arabs dominated the party, it was Shia Arabs that found themselves at odds with the party.

Why did these minority populations turn to the Ba’ath Party? In part, it was seen as a way to protect themselves from sectarian ideologies that began to grow in prominence. In particular, despite occasional references to Islam (e.g. Saddam Hussein put the words “Allahu akbar” (God is Great) on the Iraqi flag in 1991), Ba’athism was an intensely secular movement that tended to view Islam as part of Arab heritage but was not seeking to establish a religious political system. Consequently, Ba’athist governments would go on to be targets for Islamist and jihadi movements.

In 1942, Aflaq along with his associates began advocating for a pan-Arab homeland but it was not until April 1947 that the Arab Ba’ath Party was actually established, having gone from a movement to a political organisation. In the early 1950s it merged with the Arab Socialist Party and resulted in the creation of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party. In doing so, (non-Marxian) socialism became an increasingly important aspect of the pan-Arab movement in the post-war era. The party’s motto summarised succinctly their goals: “Unity, Freedom, and Socialism.” This meant Arab unity, freedom from colonialism, and social justice.

Founded in Syria, the party quickly established branches in neighbouring Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq. Meanwhile, a group of officers led by Gamal Abdel Nasser successfully overthrew the Egyptian monarchy and embraced pan-Arab nationalism, which contributed to the growth of Arab nationalism across the Middle East by virtue of Nasser’s personal popularity throughout the region. Though initially skeptical, the Syrian Ba’athists embraced the Nasserist vision and began pushing for an Egyptian-Syrian union.

Nasser accepted the formation of such a union, which would ultimately be named the United Arab Republic (UAR), but with one condition: all Syrian political parties would need to be dissolved and replaced by a single mass party. Optimistic about their future political fortunes, the Ba’athist leaders accepted without properly consulting others, resulting in the de facto dismantling of an effective party apparatus. However, the union would prove to be short-lived, lasting merely between February 1958 and September 1961. Rivalry between Egyptian and Syrian officers and concerns about the former’s hegemony within the union led to a Syrian secession, by which point the Ba’athists had become significantly weakened despite their initial significance.

Though artificial, the colonial-era borders would prove to be resilient. A few months after the UAR’s founding, Iraq had its own military coup, which ended Hashemite dynastic rule. While many of the coup participants were keen on joining their Arab brothers in the union, Abdul-Karim Qasim, the new leader of Iraq, managed to marginalise the Ba’athists and the other pan-Arab nationalists in a bid to strengthen his own grip on power.

Despite these failures, the pan-Arab ideology espoused by the party would prove to have a long reach. The nascent education systems in these Arab countries often had teachers that advocated Arab unity. One student that joined the party while in secondary school and would go on to study at a military academy was a young Syrian by the name of Hafez al-Assad (born in 1930). He came of age during a period in which coups became a frequent occurrence. They happened in 1949, 1951, 1954, and 1961 (along with later ones in 1963, 1966, and 1970).

In the two countries where Ba’athism took hold—Iraq and Syria—the military would prove to be key to the rise of the party. The military offered young and disempowered men (including from minority backgrounds) a path towards genuine social mobility. Ba’athism was particularly attractive to those from poorer backgrounds since it promised a future that was not dominated by entrenched elite interests, many of which had survived the late Ottoman period as well as the European colonial era as well with their own positions secured.

Following the demise of the UAR, several Ba’athist military officers, including Assad, along with non-Ba’athist supporters managed to seize power in Syria on March 8, 1963. Subsequently, the non-Ba’athist elements were purged. However, a schism emerged within the revived party between those who focused more on pan-Arabism and those that prioritised economic and social development. This resulted in yet another coup in February 1966, which resulted in the ousting of Aflaq and his allies, who fled to neighbouring Iraq. This also signalled the break within the party between a Syrian branch and an Iraqi branch. Despite the events of 1966, internal factionalism continued to plague Syria. Assad, who had been defence minister during the disastrous Six Day War with Israel, sought to prevent his own marginalisation. Anticipating his own imminent sacking, Assad carried out the “Corrective Revolution,” a bloodless coup that sought to ensure his own position while ending the ongoing factionalism.

In Iraq, things would prove to be quite unstable as well. Following the ending of the monarchy in 1958, Qasim’s relationship with the erstwhile Ba’athist allies would quickly break down. In addition to his efforts to consolidate his power, Qasim leaned towards Iraq’s Communist Party while being rather tepid in his support for pan-Arabism. This resulted in a failed Ba’athist assassination attempt on Qasim’s life in 1959 that also involved a young man who subsequently fled the country. That man was Saddam Hussein. Unsurprisingly, Qasim cracked down on the party but the Ba’athists managed to recover and take power in February 1963, resulting in Qasim’s ultimate downfall and execution.

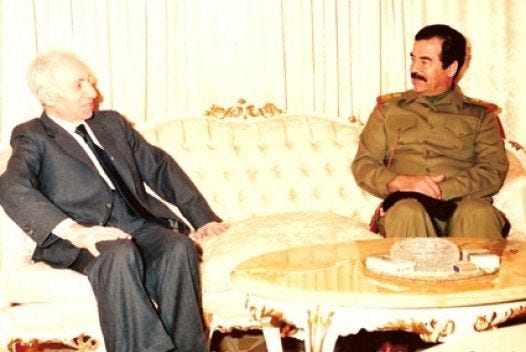

But like their Syrian counterparts, the Iraqi Ba’athists suffered from internal disputes and were themselves ousted. Nonetheless, they managed to make a comeback in July 1968 with the country subsequently headed by Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr. In a bid to secure legitimacy during the Ba’athist schism, al-Bakr and his trusted ally Saddam Hussein solicited the support of Aflaq and his associates.

The 1970s represented periods of social advancements in both countries. Investments were made into improving the lives of citizens, especially in healthcare and education. During the late 1970s an effort was made to reconcile the two branches and even unify Iraq and Syria. With al-Bakr and al-Assad at the forefront, such a unification would have marginalised Saddam Hussein. In a bid to avert this, Saddam managed to effectively force al-Bakr out of power and thereby ascend to the top. Subsequently, a “plot” was alleged to have been discovered but was essentially a ploy to that enabled Saddam to carry out a purge in order to ensure his own position.

With the last likely bid at pan-Arab unity foiled, the two countries went their separate paths. Both Ba’athist parties maintained their hegemonic positions but both countries had effectively been turned into personalist dictatorships. By the middle of the 1980s there were 100,000 full members of the party and 400,000 candidates in Syria while Iraq had 25,000 full members and 1.5 million candidates. The parties continued to play important bureaucratic roles, with membership often being sought out in a bid to improve one’s career prospects as opposed to largely ideological motives as in earlier decades. While both Hafez al-Assad’s Syria and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq continued to espouse pan-Arab rhetoric, they increasingly turned towards more national history, such as the Palmyrene Queen Zenobia or the Babylonian Nebuchadnezzar II, respectively.

Suggested readings:

https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095438741

https://www.encyclopediaofmigration.org/en/the_bath_party_in_iraq/

http://albaath.online.fr/English/index-English.htm

https://www.encyclopediaofmigration.org/en/the_bath_party_in_iraq/

https://www.newarab.com/analysis/history-iraq-syria-relations

Nice piece. Maybe, one reason that I can add could be the incapacity of this movement for really cohesionate people and interests. Islamic movements, on the other hand, are (and were) able to produce that union in a higher degree.

It is logical, and useful as "social cohesion glue", the anger after colonitzation, but once is over and while time is passing, that "enemy" that make us "together" lose his value. Also, the arabic aspect that you mentioned that included minories for the opposition to Islamic is not so strong, because at any time ethnic differences could start and "break the tie" of the arabic identity. (I mention arabic and regret of colonies, because are the key elements of "us/good" and "them/enemy/bad".)

Islam, with its universal doctrine doesn't have this problem. Islam is attractive to people in a similar way to democracys, because attack political power and elits in name of the government of "we, the people". Islam appeals to community. These works very well if there is poverty, inestability, chaos and repression (all ingredients of all the regimes that have been falling in the recent years, for many, many reasons). Also, it is in higher level that racial ethnicity (the kurds are an exception, we can say) and racial differences are subsumed on the shared identity of muslim (sunnies or chiis according to the case). The development on the region could be explained, on one factor (there are a lot), by difference in capacity of add people to their cause, making "less important" their differences, of the pan-arabist groups and islamic groups.

Sorry for my English, I hope it is clear.