For several centuries, Austria was a leading state in Europe. Ruled by the Habsburg dynasty, the country had served as main hegemonic power in central Europe as well as the most prominent state in the Holy Roman Empire. However, throughout the nineteenth century, the country continued to diminish in stature due to the strengthening of Prussia as well as the emergence of several forms of nationalism.

Ruled by a German-speaking elite, Austria was in fact a multilingual and multicultural empire. Within the empire lived millions of subjects ranging from Germans to Croats to Italians to Poles to Czechs, among many others. Growing tensions, however, risked undermining the stability of the empire. Reforms were enacted, such as the establishment of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1867, which provided the “Hungarian” half (which also included parts of modern-day Slovakia, Romania, Serbia, etc.) a separate parliament and constitution while still sharing a monarch, foreign policy, and military with the “Austrian” half. Even within the Austrian portion, greater rights were afforded to the Emperor’s subjects, such as the right to use their languages in government institutions, etc. However, this was insufficient to prevent the empire’s disintegration following the end of the First World War. Separatism, such as among the Italian population in Milan, led to the loss of some territory even before the war had begun.

Alongside the internal dimensions was the the pressure faced by growing Prussian influence. While Austria eventually became allied with its northern neighbour during the Great War, Prussia was not always viewed favourably. Rather, it posed a challenge to Austria’s role as the leading German state in Europe. The debate on German nationalism was divided into two factions, those advocating Grossdeutschland (Greater Germany) and those calling for Kleindeutschland (Lesser Germany). This question centred on whether or not include Austria in a Germanic union or not. The establishment of the Zollverein, a customs union of German-speaking states that excluded Austria, as well as the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 (sometimes also called the Fraternal War in German), which pitted Prussian-led German states against Austrian-led German states against one another, reflected the seriousness of what was called ‘The German Question.’

On the Austrian side, unity was not usually the case on the issue. For the rulers, a union with a Prussian-dominated German state risked marginalising Vienna’s power. However, genuine support did exist amongst the pan-Germanists. At times, this resulted in surprising ideological overlap. Socialists such as Karl Renner, who went on to be the first chancellor of the First Austrian Republic, as well as the right-wing mayor of Vienna Karl Lueger.

Post-World War One

Following defeat in the First World War, Austria was a shadow of its former self. With the loss of most of its non-German speaking territories, including some of the German-speaking as well (South Tyrol in Italy, Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia), and suddenly landlocked, the viability of the new Austrian state became intensely debated. The redrawing of the map in 1919 by the major powers prevented a possible union between Germany and German Austria. While this veto, which went against the majority wishes in both countries, ran counter to the idea of national self-determination that was granted to former constituent elements of Austria-Hungary, the fear of German revival still ran higher among the victors.

For many in Austria, there seemed little hope for the state if it were to exist outside of Germany. Aside from being landlocked, the country had also lost much of its industry, which found itself in what was previously Bohemia and by now Czechoslovakia. Additionally, cultural affinity and similarity with the South Germans, such as Bavarians, ran strong. For many, unification was an obvious way forward.

While this was not immediately possible, it did not result in an abandonment of pan-German sentiments.

Austrofascism

Austrofascism–a heavily contested term–developed out of two strands. The first was the Christian Social Party, which existed during the Austro-Hungarian Empire and was the leading conservative party for much of the latter days of the empire and stood in opposition to the socialist movements that grew in the 19th century. However, arguably more dominant was, as the name suggests, Italian fascism. At its core, it was an anti-left wing and reactionary force that sought to prevent leftist revolutions, which had briefly taken hold in neighbouring Hungary and Bavaria, where Soviet republics had temporarily been established.

Like its Italian predecessor, Austrofascism was corporatist in nature but far more clerical. Central to it was the preservation of Austria as a Catholic country, which differentiated it from neighbouring Germany, where though it had a large Catholic population was traditionally-speaking politically dominated by northern/Prussian Protestants. Social teachings from the Church were heavily promoted and was the basis of moral and political education. This trend was not unique to Austria but also applied to other countries in the 1930’s, such as Portugal and Spain. The clerical nature of the ideology pushed for not only social conservatism but also criticised modernity, capitalism, democracy, and leftist beliefs.

Corporatism, not to be confused with corporatocracy (rule by corporations), is the ideological foundation that describes different strands of fascism but Austrofascism in particular. Whereas communism advocated class conflict, corporatism called for class collaboration. It saw the nation as a corpus (a body) in which all the elements, whether employers or employees, are essential organs and that only by having all in harmony can the country prosper. Similar to its Nazi cousin, Austrofascism was ostensibly opposed to both ‘Bolshevism’ as well as ‘plutocracy.’ Vocabulary was strikingly similar, with both calling for the preservation of the Volksgemeinschaft (national community).

Richard Streide, the leader of the paramilitary Heimwehr (an Austrian version of the Freikorps), put it this way: “We reject western democratic parliamentarianism and the party state!... We are determined to put into its place the self-government of the Estates and a strong leadership which develops, not from the representatives of the parties, but from leading personalities of the large Estates. [...] We are fighting against the subversion of our nation by the Marxist class struggle and the shaping of the economy by liberal capitalism.”

Even more explicitly, Federal Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss proclaimed that "The time of the capitalist system, the time of the economic system based upon Liberal and Capitalist principles, is past. The time of Marxian and materialistic government is over. Party domination is no more! We reject enforced political conformity and terror. We want the social, Christian, German state of Austria based on corporative principles with a strong authoritarian leadership! Authority does not mean despotism, authority means orderly power. It means leadership by responsible and unselfish men willing to make sacrifices …"

Establishing a Dictatorship

Politically, Austria was not spared the instability that came to define interwar Europe more broadly. This became especially acute in 1933. On 4th of March of that year, the National Council (the lower house of the Parliament) was debating the ongoing railway workers strike that had to be ultimately resolved by a vote, which was expected to be extremely close. Austrian parliamentary rules prevented voting by the president of the National Council, who was himself an elected member, which led to all three presidents (Karl Renner (Social Democrat), Rudolf Ramek (Christian Social Party) and Sepp Straffner (Greater German People's Party)) resigning in order to participate in the vote. This created a problem. Procedurally, there had to be a president in order for the vote to take place but with none in place, the parliament had effectively become paralysed.

Dollfuss, considering the ongoing crisis “not provided for in the constitution,” intervened and ended what would be the last session of the Council until 1948. Based on the Wartime Economy Authority Law, which was passed in 1917, Dollfuss seized power following what he termed “Selbstausschaltung des Parlaments” (the self-elimination of the Parliament). Despite the euphemistic term, it was effectively a coup d’état. The law effectively curtailed freedom of the press and freedom of assembly and started the process in which Austria became a dictatorship.

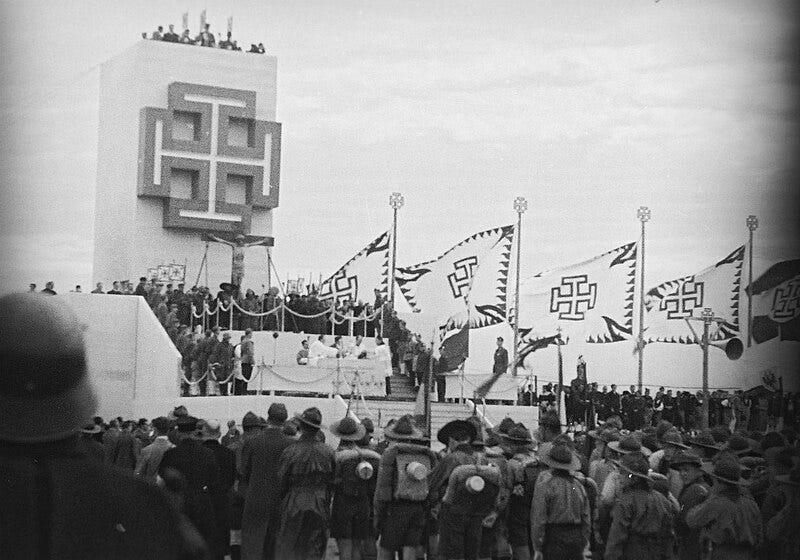

While Social Democrats were opposed by Dollfuss, with their paramilitary wing Republikanische Schutzbund being banned (though still operating illegally), they were not the only opponents. As an Austrian nationalist, Dollfuss was strongly opposed to Nazism, which sought to unite Austria and Germany. Following the communal elections in Innsbruck in May 1933, which saw the Austrian National Socialists gain 40% of the vote, the chancellor took even more drastic actions. He banned state and communal elections, which was ostensibly a temporary measurement but in fact became permanent. Additionally, Dollfuss sought to increase his power by combining the forces of Christian Social Party and the Heimwehr into the Vaterländische Front (the Fatherland Front), which became the sole legal political party in the country.

By February 1934, the new government had yet to completely consolidate power completely. Social Democrats were still taking to the street, at times armed. That month, over the course of a few days, right-wing and and left-wing forces clashed in skirmishes in what is called the Austrian Civil War. Though it lasted less than a week, the crackdown by government forces on the opposition reaffirmed the end of multiparty parliamentary democracy as well as the authority of the new government. A few months later, Dollfuss, who had until then ruled by decree using emergency powers, formally established the May Constitution. In addition to abolishing democracy, the new constitution formalised the role of the Catholic Church and proclaimed that all laws came from God and affirmed that Austria was a Christian state. At the same time, the chancellor continued his anti-Nazi policies with the aim of preserving Austrian independence.

The Italian Dimension

In neighbouring Italy, Mussolini embraced the new ruler of Austria. In many ways, Dollfuss became an Austrian counterpart. More importantly, however, was the fact that Austria acted as a buffer state between Italy and Germany. The later establishment of the Axis Powers, coupled with Hitler’s early admiration for Mussolini, should not lead one to assume that this was true the other way around early on. Rather, German Nazism was in some ways antagonistic to Italian fascism. In terms of racial ideology, which hadn’t quite taken hold in Italy yet, the Nazi belief in a superior Germanic race, i.e. the Aryans, went against notions of Italian exceptionalism. Indeed, Mussolini even openly rebuked the notion when he proclaimed that ‘Thirty centuries of history allow us to look with supreme pity on certain doctrines which are preached beyond the Alps by the descendants of those who were illiterate when Rome had Caesar, Virgil and Augustus.’

More relevant, however, was the concern about Italian territorial integrity. In the northern part of the country lives a sizeable German minority, which constitutes a majority in South Tyrol. Whereas Hitler was an expansionist, Dollfuss was not. Consequently, the Austrofascist government provided Italy with breathing space. On 13 April 1933, Dollfuss and Mussolini met for the first time in the city of Rome whereby the Italian ruler pledged that “if necessary, Italy would defend Austria’s independence by force of arms.”

This position was not uniquely held by Italy in regards to its relationship with Austria. Rather, it was part of a wider anti-German policy held by Il Duce, which gradually ceased to exist. As late as 1935, Mussolini joined the Stresa Front alongside French prime minister Pierre-Étienne Flandin and British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald in which they promised to maintain the post-war treaties regarding the borders in Europe as well as preserve Austrian independence. Though this ultimately collapsed shortly after, as a result of disagreements caused by Italy’s invasion of Abyssinia, it was not a fluke but reflected a wider a policy position that was held by Fascist Italy for several years.

The July Putsch

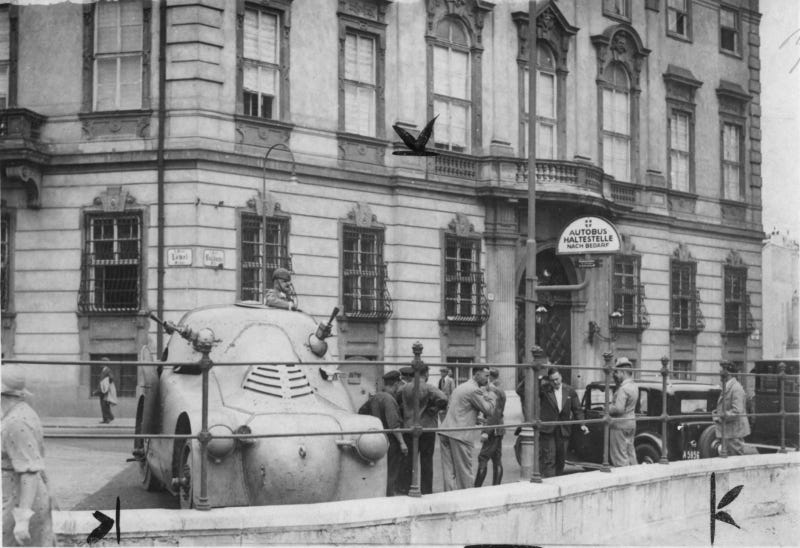

While Dollfuss’ conduct had gained him support from his southern neighbour, it had only caused considerable ire to the north. With this backdrop, Nazi Germany covertly supported Austrian Nazis in their attempt to carry out a putsch on 25 July 1934. As Hitler makes clear in Mein Kampf, Autro-German unification was of the highest priority for the Austrian-born Führer. As mentioned earlier, support for such a union was high in the country with support for the Nazis in particular also increasing. On that day, Austrian (specifically Viennese) Nazis entered the Chancellery and successfully killed Dollfuss. Despite the successful assassination, the putsch failed. With Mussolini denouncing the killing and even threatening to mobilise his army in defence of Austrian independence, the German government quickly backed down. Some of the Austrian Nazis were arrested while others managed to flee to Germany. If anything, the attempted coup had backfired and bolstered those who advocated continued Austrian independence.

Further Readings

Gunther, John. “Dollfuss and the Future of Austria.” Foreign Affairs, vol. 12, no. 2, 1934, pp. 306–318.

Redlich, Joseph. “German Austria and Nazi Germany.” Foreign Affairs, vol. 15, no. 1, 1936, pp. 179–186

Thorpe, Julie. “Austrofascism: Revisiting the 'Authoritarian State' 40 Years On.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 45, no. 2, 2010, pp. 315–343.

Rabinbach, Anson. “The Austrian Civil War of 1934: Harvard and Vienna Conferences.” International Labor and Working-Class History, no. 25, 1984, pp. 98–100

Zurcher, Arnold J. “Austria's Corporative Constitution.” The American Political Science Review, vol. 28, no. 4, 1934, pp. 664–670.

E. M. “The Independence of Austria.” Bulletin of International News, vol. 11, no. 4, 1934, pp. 3–10.

Habtom, Naman Karl-Thomas, “When Failed Coups Strengthen Leaders.” War on the Rocks, https://warontherocks.com/2023/07/when-failed-coups-strengthen-leaders/

Hitler's ten-year war on the Jews / Institute of Jewish Affairs of the American Jewish Congress, World Jewish Congress

https://www.wien.gv.at/english/history/commemoration/end-democracy.html