Having a strong economy is universally seen as desirable. However, if the goal is to recruit large numbers of people a vibrant economy could be a double-edged sword and prove to be a barrier to increasing volunteer enlistments. So how much would need to spent on soldiers’ pay?

The Russian economy is too strong for its military campaign in Ukraine. An odd claim given all the predictions that Russia was on the brink of economic collapse due to historic Western sanctions. Conventional wisdom is that economic warfare is necessary in order to degrade a country’s capacity to wage a conflict. Despite Western expectations, the Russian economy has managed to chug along at an impressive rate, even overtaking the German and Japanese economies (when measuring GDP by purchasing power parity). However, this has limited its ability to enlist men into its ranks. In fact, having a strong economy is a hindrance to large-scale military recruitment.

The biggest challenge currently facing the Russian economy across all sectors is a labour shortage, which has negatively affected recruitment. Unemployment is at a historically low 2.6%. At the same time, real wages have grown considerably as the labour market has tightened due to growing demand in the industrial sector as caused by increased military expenditure. The result? Soaring salaries, signing bonuses, and benefits, including preferential bank loans, have been doled out to those that enlist.

This raises the question of whether an economy can be too good if it is expecting to fight a major conflict. While the Russian Federation has managed to grow its standing army while sustaining significant casualties, it has not been cheap and has required a significant society-wide reorientation of the economy. But what about other countries?

Generally speaking, those countries with the largest shares of the population in the military tend to be relatively poor:

The same holds true for those whose armed forces have grown the most between 1991-2020 as a share of the total labour force:

Exceptions do exist, of course. Notable examples are countries like Israel, Greece, and South Korea, but all three have mandatory military service as do their poorer counterparts like Eritrea and North Korea. (It is also worth noting that those with the smallest shares are often also among the world’s poorest. Having an army is an expensive endeavour, after all, and a basic level of state capacity is a prerequisete.)

In its 2022 Nuclear Posture Review, the US Department of Defense predicted that “By the 2030s the United States will, for the first time in its history, face two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries.” For some, the natural conclusion has been that the United States should be able to have the capacity to fight two major wars simultaneously and that having “a one-war standard could actually make a two-war scenario more likely.” Putting aside for the time being the risks involved in such a strategy, it is not obvious that the United States with all of its wealth could create a viable and large standing army in peacetime to meet such a requirement through conventional means.

The problem the US faces is not purely economical. Most citizens are unfit for military service. According to the Center for Disease Control, “Only 2 in 5 young adults are both weight-eligible and adequately active to join the military.” When including other metrics, such as the lack of educational qualifications, having a criminal record, being prescribed some types of medications, etc., this figure is closer to 29% for people between ages 17 and 24. According to one DoD official, only 1% of people are both “eligible and inclined to have conversation” about military service. In order to tackle the recruitment crisis, the United States has moved to reduce standards, providing various types of waivers. The US military went from 94% of recruits having high school diplomas in 2003 down to 70.7.% by 2007, in large parts due to recruitment needs caused by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

While lowering requirements may partially fill personnel shortfalls, they may end up being more expensive in the end. Physically less fit soldiers are more likely to sustain injuries, which will have to be treated by the government while causing unnecessary disruption. During the Vietnam War Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara launched Project 100,000. The goal was to increase the number of recruits by lowering standards so that those that in the 10th to 30th percentile of the Armed Forces Qualification Test could still be deployed to Southeast Asia. The results for “McNamara’s Boys”—which included those with limited cognitive abilities and/or who were illiterate—were catastrophic. The men were three times more likely to be killed in the war, reassigned at a rate eleven times higher than other soldiers, arrested at a disproportionately higher rate, and far more likely to be in need of remedial training. The US military would have probably been better off not enlisting them in the first place.

Citizens not wanting to join the military is a perennial problem throughout the developed world. In Japan, the Self-Defense Forces recruited less than half its target (already a mere 9,245) when only approximately 4,300 signed the dotted line in a country with 125 million people in the fiscal year 2022. In their case, a current unemployment rate of less than 3% combined with a falling birth rate that is already far below replacement has further worsened Japan’s recruitment crisis. In response, according to Reuters, the Northeast Asian “will also buy more unmanned drones and order three highly-automated air defense warships for 314 billion yen that require only 90 sailors, less than half the crew of current ships.”

The story repeats itself over and over. In France the military had a shortfall of 3,000 personnel by the end of 2023. Across the Rhine, Germany saw a 7% decline in the number of applicants by August 2023 compared to the same period the year before. In Canada the situation has become so dire that aptitude tests are being ditched for a variety of roles, including intelligence officers. Australia has meanwhile opened recruitment to foreign citizens.

Even relatively poorer developed economies face similar struggles. On its face, the United Kingdom remains a wealthy country. It’s total nominal GDP is the sixth highest in the world and per capita stands at approximately $51,000. However, when looked at more closely, it is clear that while the country has a lot of wealth, its people do not. The country boasts the highest homelessness rate in the developed world (when both those on the streets and those in temporary accommodation like shelters are included) with 426 per 100,000 being homeless, compared to France’s 307, New Zealand’s 135, and Finland’s 16. Some former British colonies, such as Singapore and Australia, have overtaken the old Mother Country economically. Meanwhile, countries like Slovenia and Poland have been on track to having higher living standards than the United Kingdom.

In other words, for most British people, the country is not a particularly rich one, especially by Western European standards. While the unemployment rate is officially just above 4% there are approximately 11 million economically inactive working-age people in a country of 69 million. Despite this, the UK still suffers from a recruitment crisis. In a twelve-month period in 2022-2023, 51% more people quit the armed forces than enlisted (16,140 leaving as opposed to 10,680 signing up). While some news outlets and politicians have needlessly framed this as meaning the that the army is the smallest it has been since the Napoleonic wars—is London still ruling Canada and India?—it does suggest that even poorer developed countries are hard pressed to find enough soldiers. After all, the British government has failed to meet its own recruitment targets, which were already reduced due to budgetary constraints.

While the situation in the UK is particularly bad, it is worth noting that most EU countries are poorer than most US states and all but two are below the US average when measuring GDP per capita:

Even the top two outliers are a bit misleading. Their high rankings are partially due to international capital flows as opposed to locally generated wealth. According to the European Centre for International Political Economy:

“In Ireland, GDP is boosted by large foreign pharmaceutical and IT multinationals based in the country which, while producing goods and services in Ireland, record a significant proportion of their global profits within Ireland. The Central Bank of Ireland estimated that Ireland should instead rank between the 8th and 12th position in the EU if the relevant parts of per capita income are considered. For Luxembourg the story is slightly different. High GDP per capita is mainly due to the cross-border flows of workers in total employment, as they contribute to overall GDP but are not residents of the country.”

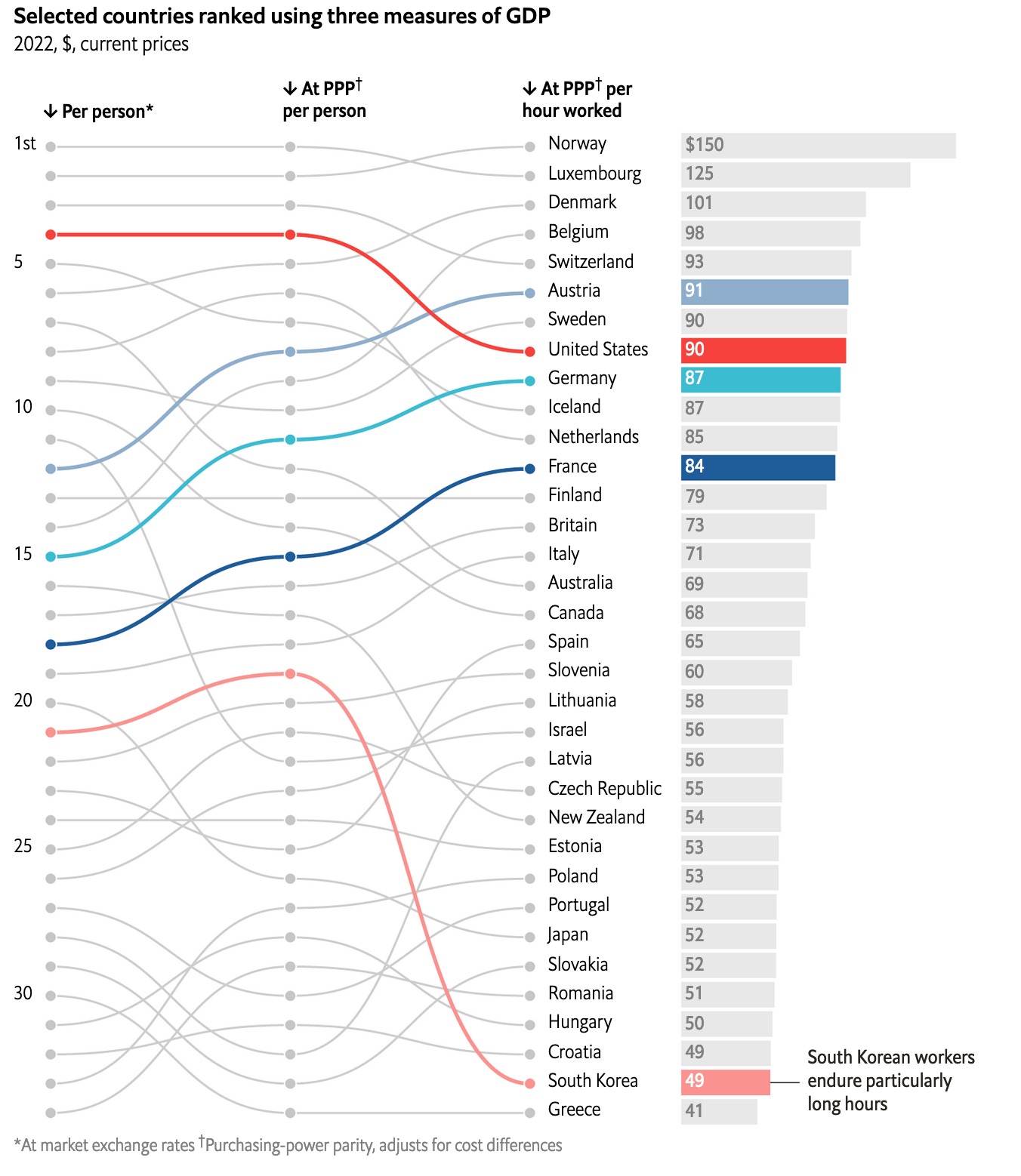

But let us compare the United States and Europe using purchasing power parity by hour worked. In this case, only the Scandinavian countries, Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Switzerland match or exceed the US. However, quite a few countries (like Germany and the Netherlands) are not far behind.

At the same time, however, the poverty rate is higher in the United States.

Theoretically, this should be an ideal situation for recruiters. Higher levels of poverty combined with greater national wealth that could be used to pay soldiers more (the US has the world’s largest defense budget by far) presumably could have alleviated the recruitment crisis, but it has not. One way to interpret the data is that even given the advantages the US posseses, military service isn’t desirable enough to allow recruitment targets to be met.

Meanwhile, while militaries have shrunk, per soldier costs have continued to increase. The average US military personnel costs approximately $140,000 with a quarter of the Defense Department’s budget going just to cash payments and benefits.

What conclusions are to be drawn from this? One is that in the absence of conscription, some combination of large economic incentives and significant levels of unemployment may be necessary. Economists sometimes talk about an optimal level of unemployment, which can be described as a level in which unemployment is not so high that it negatively impacts consumer demand but also not so low that salaries rise so high that companies are unable to hire new employees thereby being unable to respond to new demands.

The problem is that in many countries military service simply is not that attractive with many preferring whatever civilian job they can find or even unemployment over enlistment. This can be expected to be especially true during times of non-existential wars (such as those fought entirely abroad). Consequently, the financial benefits will not simply need to match those of jobs in the civilian sector but massively exceed them. Problematically for policymakers, however, is that paying more is not only expensive but even more so during times of high unemployment when the tax base shrinks while interest payments on debts could rise.

In the case of Russia, debt servicing costs have gone up but has remained manageable given that the country still can produce budget surpluses while having a low debt-to-GDP ratio (20.8% compared to the United States’ 123.3%). Its interest paid on public debt as a percentage of GDP is also relatively low:

So how much higher would a soldier have to be paid? In Russia soldiers are now being paid roughly 2.4 times more than the average salary. Assuming that a similar proportion would be necessary in the United States, where the national average salary at the end of 2023 was $59,384, this would mean more than $140,000 on salaries per soldier alone. This figure is more than $20,000 lower than the current median officer’s cash compensation of $119,800. What if recruitment happened in the poorest state in the union (Mississippi)? With $48,048 as their average salary, their enlistment would amount to $115,315 per year. Young US citizens (ages 16-24, similarly to the target demographic for recruiters) make significantly less than the average at $38,168 per year and their projected figure would still be nearly $91,600 per year.

According to the US government, the US had 1.31 million active duty personnel. Current cash compensation for the median enlisted personnel stands at roughly $67,000 per person. Assuming they were all paid on the low end at only $91,600 in cash compensation it would amount to roughly $119 billion just on salaries. Sticking with the Russian ratio in relation to the average salary (in the US case $140,000) this would amount to $183 billion. And this would only correspond with existing force levels. If the goal is truly to have more total personnel, the number would need to be even higher.

Yet the Russian figure of 2.4 times higher than the national average salary is an incomplete one. It does not include signing bonuses. In some regions, this can net a recruit more than the average annual salary before they even deploy. As a result of high salaries and signing bonuses, Russians can expect to earn more by joining the military than working in the oil and gas sector in the energy-rich country. In his 2024 budget request President Joseph Biden asked for $230 billion for military compensation, which includes non-cash compensations like healthcare and benefits for spouses and children that probably constitutes somewhere between 17% and 28% of that sum (most likely towards the higher end). If all other benefits remained the same (e.g. retirement pay), then the US government would have to spend roughly $183,000 per year on average per enlisted personnel compared to the current level of $110,000. In order to match what is happening in Russia, pay for US soldiers would likely have to be several hundreds of billions per year.

A second option is to abandon the commitment to a volunteer armed forces all together and instead revert back to conscription. The exact form varies greatly and can range from universal conscription to simply conscripting enough people to fill shortfalls. However, domestic political realities coupled with strained public finances makes this difficult. Furthermore, introducing mandatory military service could have an adverse economic effect if there is a tight labour market (but a beneficial one during periods of high unemployment).

A third option is to expand the recruitment pool. Actively recruiting foreign nationals, especially those with military experience but from poorer countries, such as Colombia, is one path. In doing so, wealthy countries can probably pay more modest sums or provide alternative benefits, like citizenship. However, these have tended to not be enough. Australia’s bid to recruit foreigners has begun by focusing on citizens of fellow Five Eyes countries (US, Canada, UK, and New Zealand) but these are also countries that already have their own recruitment crises! Elsewhere, prisoners have even been recruited in modern wars. However, these all come with their own risks.

A fourth option is to improve the quality of life for servicemen and women. Sexual assaults, food insecurity, and worsening mental health are all deterrents for would-be recruits. After all, everything is not just about money. In addition, reducing the likelihood of being deployed to war would also probably not hurt. Two decades of the Global War on Terror has hardly helped recruiters in meeting their targets.

An overlooked option is to reduce defense commitments. Instead of trying to fit the military to its ambitions, perhaps it is time to calibrate ambitions to military capabilities. As the late Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld once said (but apparently did not internalise), “you go to war with the army you have, not the army you might want or wish to have at a later time.”

If a major and prolonged non-nuclear war would break out, then perhaps the best that that each side could hope for is that they have enough people employed to produce armaments, significant youth unemployment, and sufficient amounts of money to offer generous pay for soldiers to enable recruitment while the other side has a labour shortage.

You hit on the real answer should a large-scale, conventional kinetic war break out (esp. if prolonged) - conscription (+ costly financial enticements). But that world does not show up even as a slight possibility in domestic political calculations until things get much, much worse. It's hardly economically efficient, but then again war isn't.

Here in Spain, time ago, the family tend to send the old son to the Church, the middle to the State or Administration, and the third to the Army. In villages, the priest, the school teacher and the boss of the Guardia Civil were the main figures.

You show very well how poverty is not the only issue, even maybe it is the main: in Russia most recruits are from interior "oblasts", and I think that there is a huge mass of "latinos" in the United Satets. Exists also a kind of anti-militarism huge extended, at least in Spain, and I presume that in Europe (despite the growing militarism of Escandinavian, Polish, Baltics or the British on his island; it's easy to talk about war from an island). Also, it has lost attractive and sex-appeal. Now, the cool is to be anti-militarist and pacifist (people mix anti-militarism with pacifism, what can we do....). I didn't think on the physic state of people, but it is a very good point, because the manual job is decreasing a lot, with all the issues of diet and similar that are crazy in the US.

I just discover your blog, and let me say that this first article that I've read is very good. You are watching the same issue (the problems of recruitment), but you show to us that there are many different variables that affect this. This is how it should be attached a sociological issue as this.