This is the first of a planned three-part series on the history of the Ethiopian Civil War. I originally wrote this, along with the next two parts, as a script for the documentary series ‘The Cold War.’ In this piece, I focus on the leadup to the Ethiopian Revolution.

Some Historical Context

During the Scramble for Africa during the late 19th century, the landlocked East African country of Abyssinia (the old name for Ethiopia) avoided being colonised by the nascent Kingdom of Italy, which had already gotten a foothold along the Red Sea. Despite defeating the Italians, the country was ultimately conquered by Fascist Italy during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War of 1935-6. While the sympathy remained for outmatched underdogs, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie’s appeal to the League of Nations failed to gain the necessary support to avert being taken over, in large part due to British and French desires to keep Italian dictator Benito Mussolini from sliding ever closer to Adolf Hitler.

Ultimately, London and Paris’ gambit failed as their attempt to find a compromise between Italian desires and the charter of the League of Nations by preservating an Abyssnian rump state failed to appease either side, resulting in Italy becoming an ally of Nazi Germany. During the Second World War, Italian East Africa, which was completely cutoff from the metropole, was invaded by the British, which enabled Haile Selassie’s return to his capital city Addis Ababa. Despite Soviet opposition to Italy’s expansionist war in the 1930s as well as earlier Russian support in the 19th century, the restored Ethiopian government opted to pivot westward, even going so far as to send its own soldiers on the side of the United States during the Korean War.

In 1952, as compensation and with American backing, Ethiopia was rewarded with the Italian colony of Eritrea with a federation to be established. This stood in contrast to the broader trend of decolonisation that came to define the experience of Africa during the coming decades. Just look at the cases of Italian colonies. Ethiopia was reestablished as a sovereign state, the North African colony of Libya was granted independence, while Italian Somaliland was converted into a UN Trusteeship under Italian administration in anticipation for unification with neighbouring British Somaliland and ultimately independence.

Eritrea stood apart, however. Strategically located along the Red Sea, it was Italy’s oldest colony and its most developed. During the colonial period, Rome invested heavily in its industrialisation and sent tens of thousands of settlers. The colony had been a major source for military recruitment, many of which went on to participate in the Italian invasions of Ethiopia. Eritrea also had a heterogeneous population in terms of ethnicities, with some ethnic groups finding themselves in Anglo-Egyptian Sudan while others in Ethiopia or French Somaliland (modern-day Djibouti) and a roughly even proportion of Christians and Muslims.

Considerable opposition existed in Eritrea towards the proposed federation. For one, a significant portion of the Muslim population was against the idea of being in union with an explicitly Orthodox monarchy that had subjugated its own Muslims. Christian opposition also existed, with the monarchy and nobility in Ethiopia being dominated by an Amhara ethnic elite, which did not exist in Eritrea and had similarly marginalised other groups within Ethiopia, resulting periodic waves of unrest and uprisings, such as the 1943 Woyane Rebellion, which took place in the Tigray province, bordering Eritrea. As a result, independence was a favoured path forward instead of union with a less developed and more feudal Ethiopia. Colonial veterans were particularly supportive of a Somaliland-style Italian trusteeship in anticipation for independence.

However, as the Cold War had already begun, US-backing for Haile Selassie sealed Eritrea’s fate. In addition to giving Ethiopia approximately $147 million worth of military assistance between 1953 and 1970 (constituting approximately half of all American military assistance to Africa), Washington not only had a reliable ally but also established military facilities in Eritrea, such as a listening station at Kagnew Station as well as a naval repair base at the deep water harbour of Massawa. A federation was established and a constitution proclaimed that allowed for an Eritrean assembly as well as substantial autonomy.

From Tensions to a Coup

During the federation, the Eritrean economy stagnated and entered a period of decline from its heights under the colonial period which has stimulated the economy through militarisation and infrastructural investment. The federation barely lasted a decade as Eritrea was formally annexed in 1962 and the assembly was disbanded. As a result, many Eritreans, who were already skeptical of the union, became alienated and began supporting independence.

Haile Selassie had a long reign but a tenuous grip on power. Through political machinations he became a regent in the 1920s before becoming emperor in the 1930s. However, he faced numerous threats. In 1928, supporters of Empress Zewditu conspired before launching an ill-fated coup attempt. In 1936, the Italians ousted him. In 1960 another failed coup was launched, this time also including the commander of the Imperial Guard. Beyond the capital during his time on the throne, armed revolts in various provinces broke out, including in the southeast, which were violently suppressed. However, 1974 would prove to be his biggest challenge.

Like much of the world, Ethiopia was affected by the 1973 oil crisis. Following Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War, oil-producing Arab countries announced an embargo on countries that supported Israel. Haile Selassie’s Ethiopia was one such state. This was the case for multiple reasons. Part of it was rooted in ideology, with the conservative feudal monarchy claiming direct descent from King Solomon and practiced a more Old Testament-oriented form of Christianity. More practically, Israel was seen as an ally against Arab socialist-influenced movements, many of which had an effect on the various guerrillas within Ethiopia. Israel had even trained some Ethiopian security forces. The Eritrean Liberation Front, for example, was launched out of Egypt and had support from Baathist Iraq and Syria while the Ogaden Liberation Front, operating out of the predominantly Somali province of Ogaden, got significant backing from neighbouring Somalia under the rule of Siad Barre, who became a Soviet ally. Geographically, Ethiopia was isolated. In addition to Somalia, there were also leftist (and usually Arab nationalist) governments in Sudan and across the sea in South Yemen. Even anti-communist Arab governments, such as nearby Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, provided support to leftwing Eritrean rebels.

Already suffering from an El Niño-induced famine and mismanagement, the Ethiopian government hiked fuel prices by 50%. The government hoped that the price increase would be absorbed by transport providers, thereby avoiding public anger, but this did not come to pass. Instead a strike was announced by taxi drivers in Addis Ababa, crippling the city’s economy (which already lacked a working public transport system due to government underinvestment), which in turn led to inflation and growing public anger. Other members of society, such as teachers and students, then joined anti-government protests.

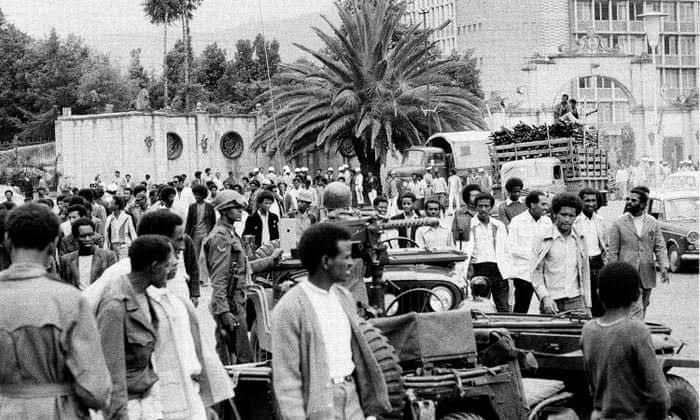

Simultaneously, a series of mutinies broke out around the country. Disgruntled soldiers and junior/mid-level officers not only complained about the lack of support and provisions (including water) provided to them but also over all government mismanagement. In the summer of 1974, some of these officers from the various branches of the armed forces (as well as the police) formed the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police and Territorial Army, more commonly known as the Derg (meaning “Committee”). In the coming months, the Derg managed to marginalise or remove several senior officials. Ultimately, on September 12th 1974, Haile Selassie himself was overthrown, resulting in the end of the monarchy.

The ousted emperor died the following year though disagreements still remain regarding his exact fate, ranging from natural causes due to his old age (83 years old) to claims that he was murdered. Nevertheless, his overthrow would have significant reverberations. First, dozens of senior political figures, noblemen, and members of the ancien régime were executed. Second, the Derg began utilising leftwing rhetoric promising land reform (as opposed to the country’s feudal structure) as well as pledging (and carrying out a successful) literacy campaign. Third, the ousting of a reliable American ally resulted in worsening US-Ethiopian relations, with the US refusing to provide weapons, ceasing aid, and withdrawing its forces from the country. Intended to weaken the country as a response to its leftwing pivot, it instead had the effect of pushing Ethiopia into the Soviet camp.

To be continued.

Suggested readings: