Is the Civilian Death Rate in Ukraine High or Low?

Trying to understand why relatively few civilians have been killed

The ongoing fighting between the Russian Federation and Ukraine has resulted in hundreds of thousands of fatalities and injuries. However, the proportion of civilians killed remains remarkably low. Why is this the case?

Reviewing the figures

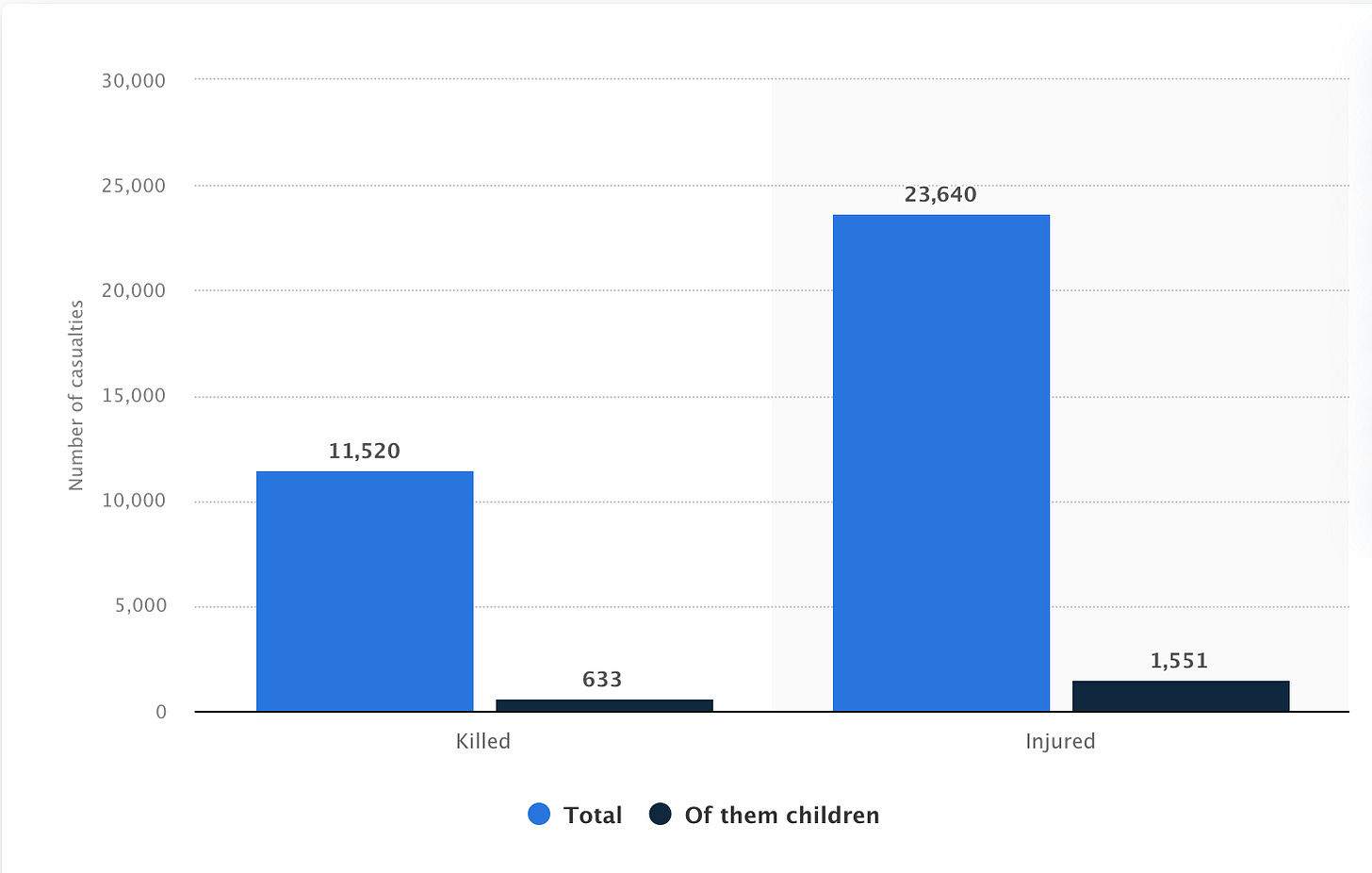

First, let’s assess the number of civilian deaths in Ukraine. Between February 2022 and February 2024, the United Nations confirmed 10,582 civilian deaths and 19,875 injured civilians for a total casualty figure of 30,457. Of course, the true number is likely higher but it is at least a start. By late October 2024, the civilian death toll (once again according to the UN) had increased to 11,973, i.e. 1,391 deaths over the course of eight months representing an overall average of 174 civilian deaths per month this year.

These figures, you may protest, are simply the verified ones but do not represent the true scale since deaths in Russian-controlled areas are not being accurately assessed. Fair enough, so let's look at another dataset.

One source that we can turn to is the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), which is based out of Uppsala University’s Department of Peace and Conflict Research and describes itself as “the world’s main provider of data on organized violence and the oldest ongoing data collection project for civil war, with a history of almost 40 years.” (Given that most wars in recent decades are civil wars this is naturally their focus but they also figures for interstate conflicts.) According to their dataset approximately 37,000 civilian and unknown deaths took place in 2022. The following year (which consists of twelve months of fighting compared to 2022’s ten months) resulted in fewer than 2,500 civilian and unknown deaths.

UCDP’s estimate for overall deaths in 2022 is 92,835 and for 2023 is 71,031 for a total of 163,866. This would suggest that civilians deaths made up about 24% of deaths over the two years. If we only look at 2023, civilian deaths constituted only 3.5% in 2023.

Another potential source that we can turn to is the Swiss-based Small Arms Survey. Looking at just Ukrainian deaths during the first year of the conflict, they estimate 87,400 Ukrainian deaths with 74.8% (65,400) being combatants, leaving 25.2% (22,000) as civilians. The Center for Strategic & International Studies put the Russian combatant casualty figure in the same ballpark (60,000-70,000) during this same time period. Given that the trend of the conflict has been one towards fewer civilian deaths as the conflict progresses, we can assume with relative confidence that 2023 and 2024 had even lower civilian death tolls. If we combine total deaths (i.e. Russian and Ukrainian military deaths and Ukrainian civilian deaths), civilian deaths make up 14.4% of all deaths between February 2022 and February 2023.

Contextualising the data

How do these civilian casualty proportions in Ukraine compare to other warzones? According to Therese Pettersson, a conflict researcher who manages UCDP, “[a]lthough there are substantial differences between different conflicts, the civilian share of fatalities has remained around 40-60% for centuries.” In other words, the Russo-Ukrainian conflict is significantly less deadly to civilians compared to the average for wars despite the scale of fighting.

This applies to ongoing conflicts. In the case of Gaza, the first twelve months of the current conflict resulted in 11,000 children being killed. In other words, four times as many children died in one year of war in Gaza (in a territory with only 2.2 million people, roughly half of whom are children) than all civilian deaths in Ukraine in 2023. This figure becomes even more stark when look at only child deaths in Ukraine.

Acknowledging that the UN-verified figures do not represent the true figure, these numbers can still tell us something about proportions. Assuming that the ratio of total civilian deaths to child deaths is accurate, then we can assume that 5.5% of civilian deaths are child deaths. Using this proportion and applying it to the UCDP number for 2022-2023 (inclusive), we arrive at an estimate of 2,173 child deaths. (For 2023 the number would be 138.) Despite this, these figures are not directly comparable as the median age of Palestinians (not just Gazans but let’s assume the numbers are roughly similar between Gaza and the West Bank) is substantially lower than the median age of Ukrainians. Furthermore, children have left Ukraine in large numbers compared to Gaza, where they remain trapped.

How many Ukrainian child casualties would there be if deaths were comparable to Gaza? If we rely on youth dependency ratio (defined as “the ratio of younger dependents – people younger than 15 – to the working-age population – those ages 15-64”) in 2021 (as a pre-war baseline for both places), we get 22.45% and 68.06% for Ukraine and Palestine, respectively. Therefore, if we triple the number of child deaths in Ukraine based on our estimate of 2,173, we would get 6,519 child deaths over the course of two years, which is still far, far lower than in Gaza just in terms of raw number let alone adjusting for population.

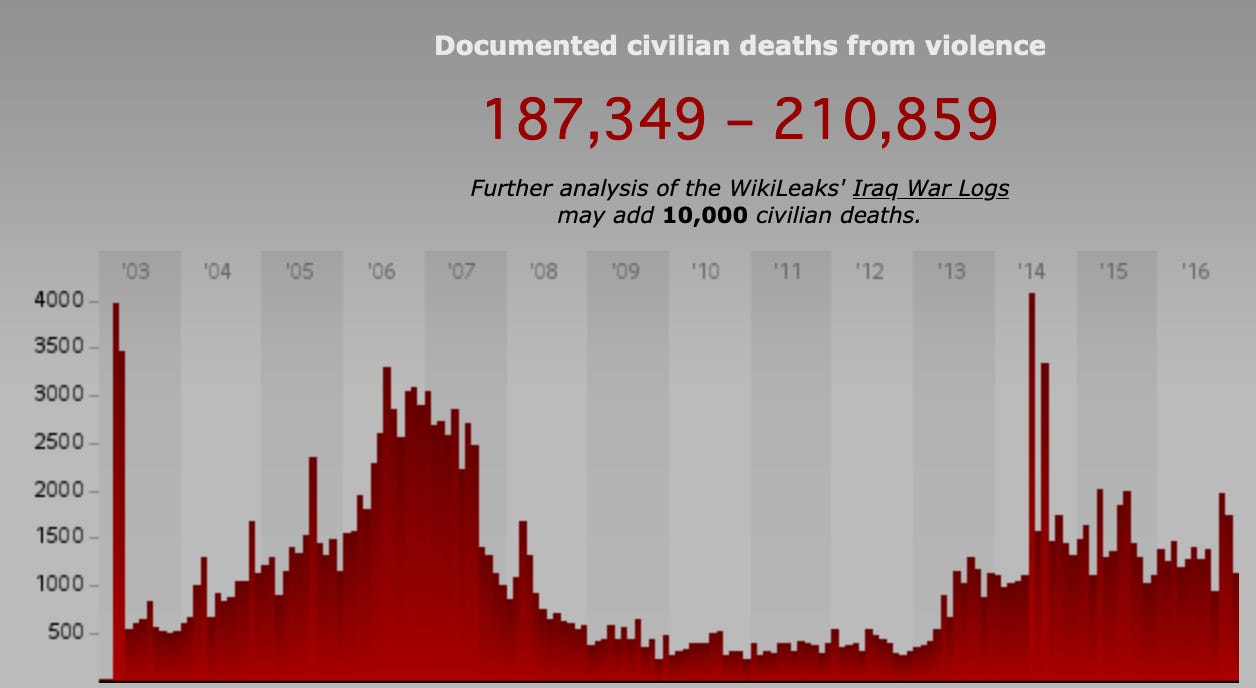

A defining characteristic of the ongoing hostilities is the state-based nature, i.e. virtually all of the fighting is between state forces and their affiliated units. This stands in contrast to most modern wars, which are mostly civil wars and tend to kill more civilians. The Iraq War is an illustrative example. The Middle Eastern conflict had three peaks in terms of civilian deaths between 2003 and 2016, which took place in 2003 (the US-led invasion), 2006-2007 (the most intense part of the Iraqi civil war during the US occupation), and 2014 (the zenith of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria). The Iraq Body Count, a public database that “records the violent deaths that have resulted from the 2003 military intervention in Iraq,” puts civilian fatalities at 187,349 – 210,859 out of a total 300,000 deaths, i.e. between 62.4% and 70.3% of all deaths in Iraq during this period were civilian.

Explaining the trend

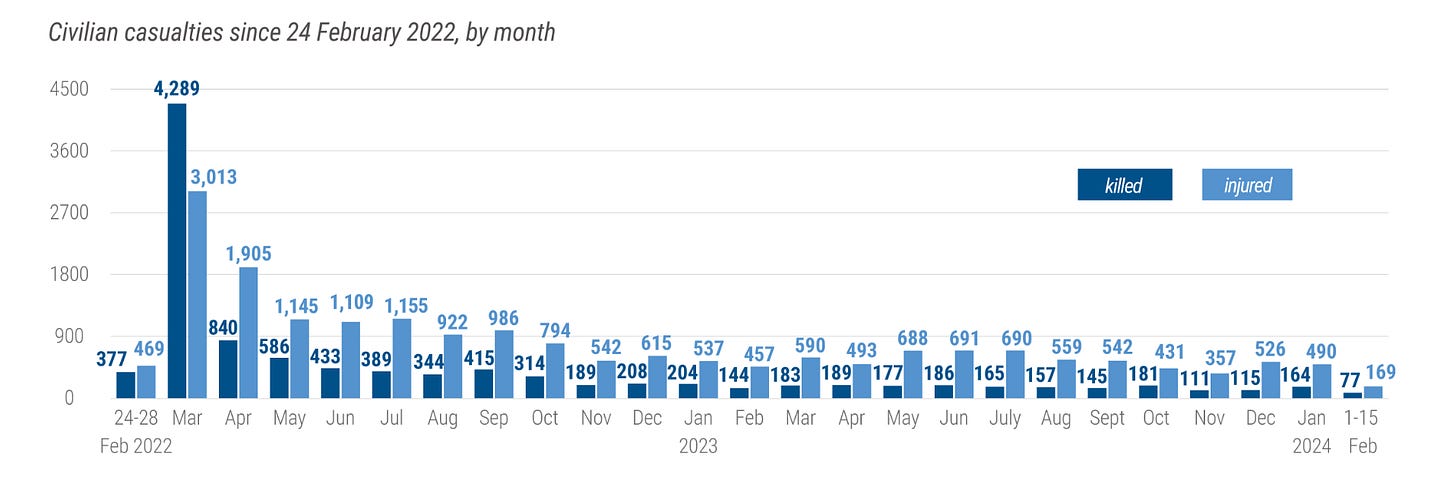

On the whole, the conflict has gotten less deadly for civilians with the progression of time. If we look at monthly civilian casualties during the first two years of the conflict, we can see that the deadliest month was March 2022. Accepting that these numbers are lower than the true figure, the trend is nonetheless clear.

This decline in civilian deaths does not reflect the overall casualty figures. In fact, combatant casualties have consistently remained high and the number of troops deployed by the two sides have grown massively since February 2022. The bloodiest battle was in Bakhmut, which took place between August 2022 and May 2023. Additionally, Ukraine’s unsuccessful counteroffensive took place in the summer of 2023. Other major battles continued to take place, like in Avdeyevka/Avdiivka (October 2023-February 2024).

So how do we explain a continuously high-intensity conflict producing relatively low number of civilian deaths? The easiest part to explain is the precipitous decline between 2022 and 2023, namely that combat took place in areas with few civilians. As UCDP explains:

“Civilian fatalities dropped as violence shifted away from major population centers such as Kyiv, Mariupol, and Kharkiv, and instead became concentrated in largely evacuated cities such as Bakhmut and Avdiivka.”

In fact, both sides have carried out evacuation of civilians. Unsurprisingly, when Russia advances Ukraine evacuates its citizens from the frontline. Even prior to 24 February 2022, separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk announced evacuations of hundreds of thousands while the partial retreat in September 2022 by the Russian military was accompanied by evacuations organised by Russian forces. (Already in July 2022 the Russian government simplified naturalisation for all Ukrainians, including those who have never lived in Russia before.)

Another explanation is that both sides are primarily focused on achieving military objectives. In the case of Ukraine this is self-explanatory as they seek to retake their territory. From the Russian perspective, mass casualties of people that are now under your jurisdiction (i.e. the four annexed oblasts) are not conducive to their long-term goals. Beyond that, the relatively static frontline produces intense battlefield needs that neither side can afford to divert. High attrition rates has meant that neither the Russians nor the Ukrainians can afford to expand their zones of operations to civilian-populated areas without risking overstretching their forces and having their own defences potentially collapse, as Ukraine’s recent Kursk incursion has illustrated.

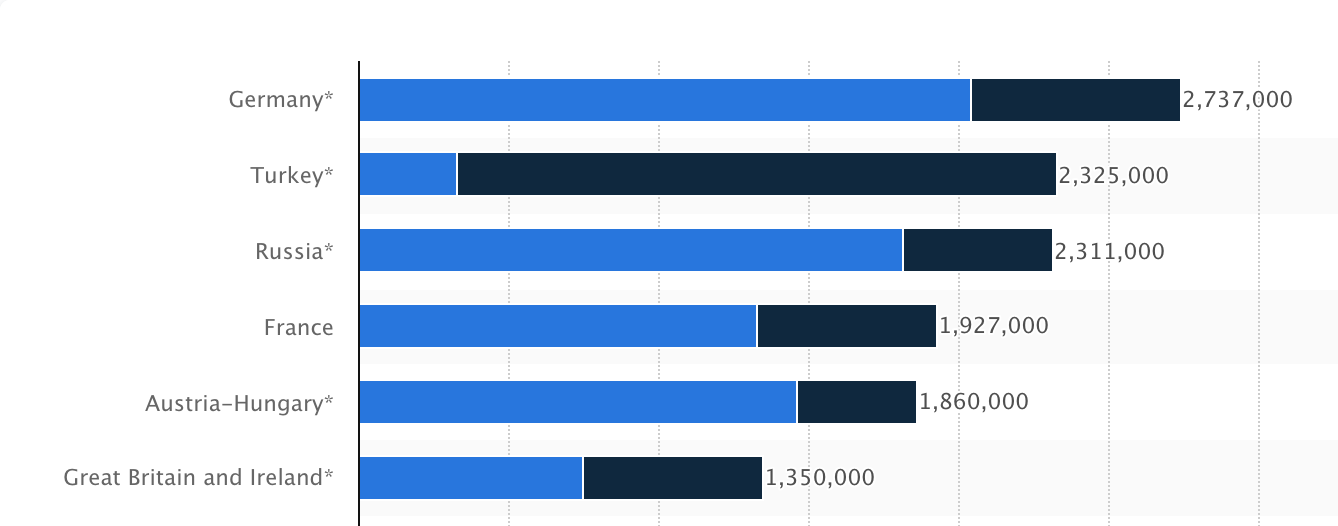

The static nature of the frontline has some historical precedent. During the First World War, the trench warfare that dominated the Western Front resulted in a similarly low civilian death rate. In the case of France, an estimated 180,000 civilians died during the Great War (including also excess deaths due to occupation conditions), constituting roughly 12% of French deaths (including those that died from the Spanish Flu). Even if you look at figures that give far higher civilian death estimates (e.g. the chart below puts French civilian deaths at 600,000), we can still see that in the top six countries in terms of total deaths during the First World War five of them had more military deaths than civilian deaths. This number is further skewed by the fact that most of the civilians that died in the United Kingdom and Germany were from hunger, many of the Ottoman deaths were Armenian (i.e. not caused by enemy forces), while the estimate for the Imperial Russian military deaths is on the lower end.

In other words, like the Russo-Ukrainian conflict, a static frontline with massive military-on-military combat results in a strikingly low proportion of civilian deaths. Given the improvements in medical care and the reduced risk of hunger/famine, it is to be expected a century after the Great War that civilian deaths can be reduced even further as a proportion.

Furthermore, despite Western media coverage, Russian warmaking is not centred around civilian targets. Even the targetting of non-military sites far from the frontline can mostly be explained by a desire to exhaust Ukrainian air defences in order to enable Russian ground forces to advance along the front while wearing down Ukrainian military capabilities. As I have written before, Russian airstrikes (both in Ukraine and Syria) are actually less deadly for civilians than US-led coalition airstrikes in Iraq, Libya, and Syria.

Caveats

Some readers may find my assessment to be far too charitable. “What about Bucha?” This case also illustrates the fog of war. Following the withdrawal of Russian troops from northern Ukraine in the spring of 2022, corpses were discovered that were quickly identified as being civilian. As the Spanish newspaper El País has reported:

“The UN mission has documented the executions of 73 civilians in Bucha – 54 men, 16 women, two boys and a girl), and are attempting to verify a further 105 cases. Local authorities put the number of people killed in the Bucha massacre at over 400.”

The discrepancy here is significant. The estimates for the civilian death toll in Mariupol is even wider. Ukrainian authorities have put the figure at 25,000. Human Rights Watch estimates at least 8,034 excess deaths, though it was unable to ascertain how many of these were civilians or combatants. Meanwhile, the UN verified “1,348 individual civilian deaths directly in hostilities in Mariupol… The actual death toll of hostilities on civilians is likely thousands higher.”

These figures only deal with direct conflict-related deaths, i.e. being killed as a result of fighting. It does not include indirect deaths, which can be the result of damage to infrastructure like the electric grid. As a result, in the long-term, the civilian deaths due to the conflict will likely be higher than those immediately registered. As such, we will only know what the true death toll after the guns go silent.

Final thoughts

The Russo-Ukrainian battlefield stands apart from other concurrent hotspots, like those in the Sahel and the Middle East. An interstate conflict fought by conventional means away from population centres in territories they both view as integral and vital has produced a remarkably low, though still tragic, number of civilian deaths. A closer examination of the available data suggests that the hostilities, especially from 2023 onwards, represents as pure of a state-on-state conventional war of a significant scale that one can expect.