The Brazilian-Argentine Nuclear Weapons Rivalry

Why two neighbours pursued the bomb even though neither really wanted it

This text was originally written by me for the online documentary series ‘The Cold War.’

Nuclear weapons have been developed by countries in North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa as well as tested in Australia. Absent from this list is South America, but this was not a given. While nuclear bombs during the Cold War are often associated with ideological rivals, such as the United States and the Soviet Union, it was not necessarily seen that way at the time. In fact, for some countries, nuclear weapons were seen as something to potentially possess against a regional rival. This was certainly the case for Brazil and Argentina.

Brazilian Desires

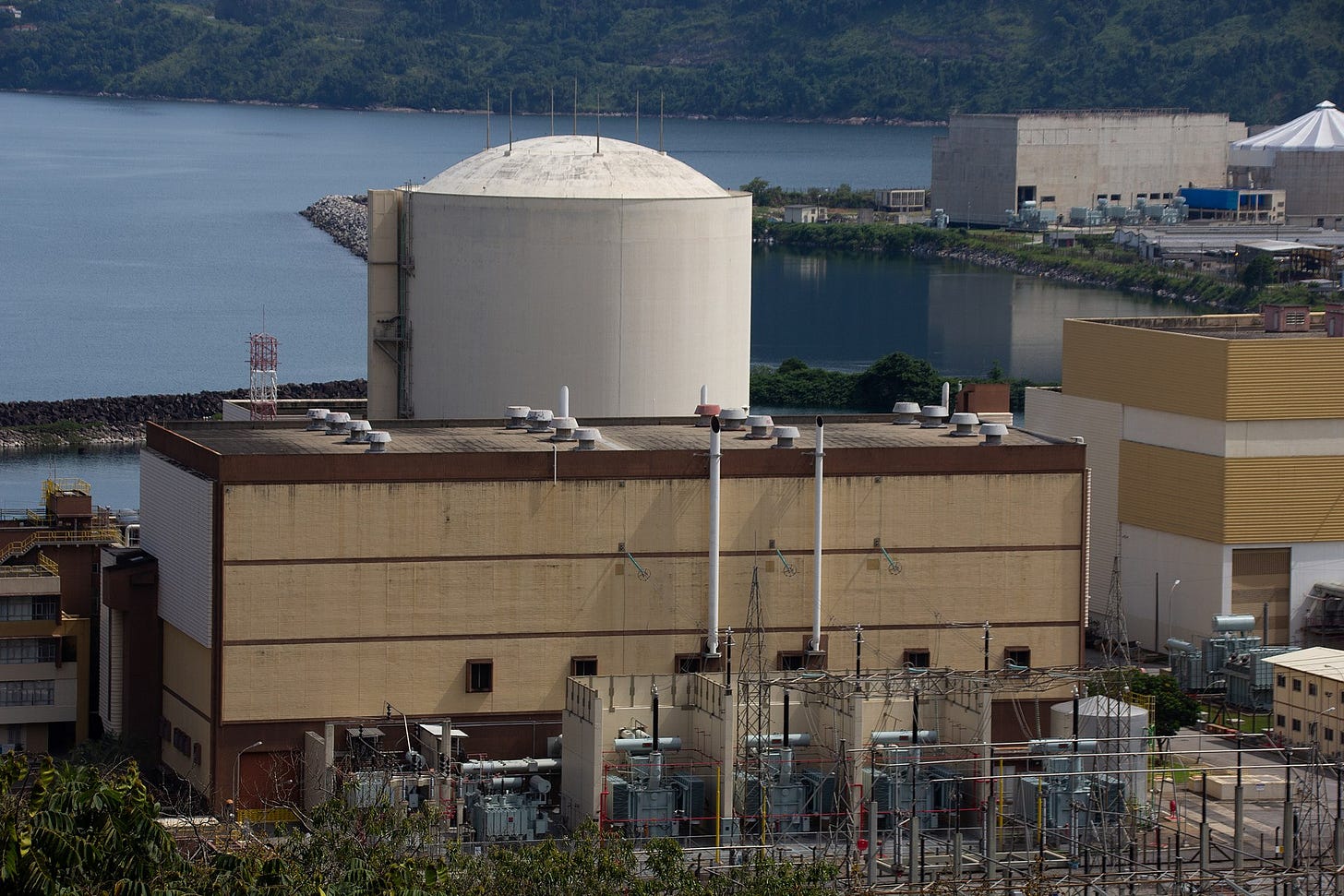

Brazilian scientists first began researching nuclear fission as early as the 1930s. Beginning in the 1940s, Brazil signed a series of agreements with the United States, initially dealing with mining but eventually would result in a US pledge to transfer nuclear technology to the Latin American giant. In 1965, with the Brazilian military having seized power the previous year and establishing military rule that would last over two decades, Brazil and the United States signed an agreement whereby the latter would provide a nuclear power plant to the former, with the Angra I reactor being supplied in 1971.

While the United States, as a superpower and the Western Hemisphere’s hegemon, was an obvious partner in Brazil’s nuclear (albeit so far non-weapons) aspirations, it was not the only one. Initially, in the early 1960s Brazil looked to France as a possible source for a uranium-powered nuclear reactor though these efforts were abandoned in 1964. In 1975, Brazil and West Germany signed an agreement whereby Brazil would obtain ten nuclear power plants, on the condition that they were subject to International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards. Ultimately, these efforts, too, failed to reach the goals the Brazilian government had set out for itself, partially as a result of American pressure. Suspicions about a weapons programme led Washington to block the export of some technologies, such as high-speed computers, which negatively impacted universities, the national oil company Petrobras, and the National Space Research Institute.

Instead, parallel to the civilian bilateral project, the Brazilian government initiated a covert programme code-named Solimões Project. Rather than creating a standalone programme, it incorporated efforts of all three branches of the armed forces. The Navy was tasked with making ultracentrifuges for uranium enrichment, the Air Force with research on laser enrichment of uranium, while the Army focused on graphite reactors in order to make plutonium. Though the military government hoped to involve all three branches, ultimately only the Navy (cooperating with the Institute for Energy and Nuclear Research (IPEN)) was successful with their MIT-trained officers and essentially dominated the country’s secret parallel programme.

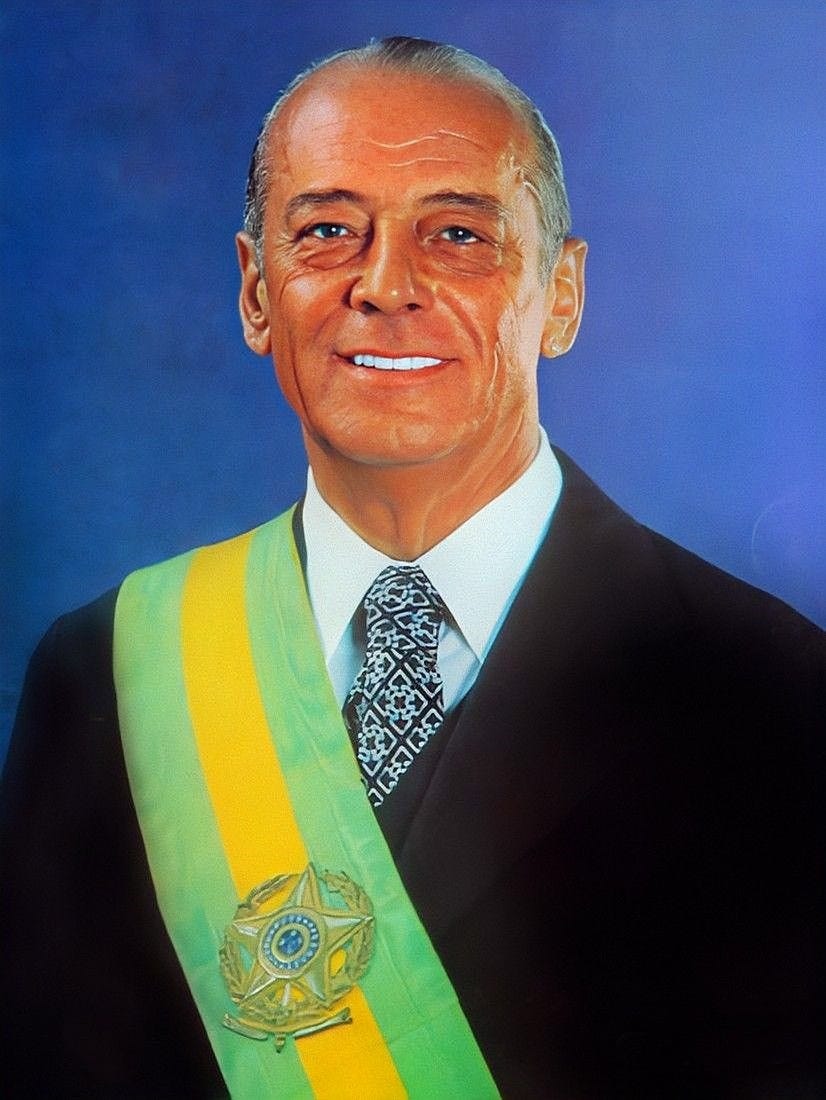

The secret programme to enrich uranium, officially called the Autonomous Program of Nuclear Technology (PATN), was approved in the late 1970s by President João Figueiredo and was guided by a number of factors. For the Navy, it helped advance its ambition to build nuclear powered submarines. Additionally, the ability to enrich uranium was seen as a status enhancer, thereby elevating Brazil’s position in the international community through prestige. Additionally, the oil crisis that began in 1973 illustrated how unpredictable global energy supplies were. (Though some believe the oil crisis was merely an excuse since the electricity grid was mainly reliant on hydropower and that oil was still necessary for transportation and industrial needs.) One of the main motives was Argentina’s concurrent nuclear programme. Not only was Buenos Aires’ programme seen as a threat but it was hoped that by showing comparable skills Brasilia’s own efforts would deter their Spanish-speaking neighbours from continuing with their programme.

Argentina’s Pursuit

Argentina’s first dalliance with all things nuclear began in the 1940s with some scientists who had previously worked in Nazi Germany. Austrian-born German scientist Ronald Richter moved to Argentina at the invitation of Kurt Tank, an aeronautical engineer who had previously headed Focke-Wulf (1931-45) before being appointed head of an aerotechnical institute in Argentina. Tank arranged a meeting where Richter managed to convince Argentine president Juan Perón to back his plan of constructing a nuclear fusion reactor, which Richter claimed could help solve Argentina’s energy needs. Excited by the prospect, Perón poured hundreds of millions of pesos into the project, which operated on an island in Patagonia’s Nahuel Huapi Lake. As scepticism grew within the Argentine military and scientific community grew, Perón commissioned a board to produce their own reports on what became known as the Huemul Project. Having failed to achieve fusion, Richter’s project was abandoned. In 1955, Perón was overthrown in a military coup and Richter was even arrested though he was eventually released.

In the 1960s Argentina launched a more conventional nuclear energy programme and was deemed to be at least a decade ahead of any Brazilian efforts. The Argentines were motivated by many of the same things as their lusophone neighbours, namely a desire for prestige, regional rivalry, and a want for what was deemed a First World technology. Even though they did not explicitly state that their goal was to obtain nuclear weapons, the Argentines also wanted to preserve the option to get them at a later time. As a result, Argentina did not sign the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons and also refused to join the 1967 Treaty of Tlatelolco, which established a nuclear weapons-free zone in Latin America. Additionally, Argentina had a tenuous relationship with democracy and civilian rule, falling back under military rule in March 1976 with the ousting of President Isabel Perón, which resulted in a continued militarised approach to security.

In addition to nuclear development, the two countries also pursued a series of practical steps should they actually build a nuke. For example, Brazil built a 300 metre deep underground testing site in the Amazon in the State of Pará. Argentina, meanwhile, had a medium-range ballistic missile programme, called Cóndor II, which was made possible due to some European financial investment as well as support from Egypt, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia.

We must so they don’t!

So why did the two countries decide to embark on this path? Neither country was intrinsically interested in nuclear weapons and there was no imminent danger of conflict either. The underlying motivation was rooted in a concern that the other country may obtain one. As Brazil’s Navy Minister Fonseca put it, “We don’t need the bomb now, since there is no foreign enemy in sight. What we need is to retain the technology to have the capability to fabricate it should circumstances require.” That logic applied not only north to south but also south to north. For Argentina, geographically and demographically smaller than Brazil, nuclear weapons were seen as a potential equaliser, but with the exception of a small fringe of genuine nuke advocates, this equalising potential was mainly conceived in the case where Brazil would obtain such weapons. This resulted in both countries pursuing a policy of hedging, i.e. wanting to have the ability in case the other goes all the way

Near-simultaneously democratisation in both countries resulted in the end of any pursuit of nuclear weapons capability. In Argentina, the Falklands War—in which the Argentines sought to seize the British controlled Falkland Islands (or las Malvinas, as the Argentines called them)—turned into a debacle that critically weakened the ruling military, resulting in the return of democracy in 1983. As a result, nuclear development was placed under civilian control. Meanwhile, in Brazil, the military government that had existed since 1964 was beginning to crack. Economic and social crises began to compound, particularly in the 1970s and into the 1980s such as a result of the 1979 petroleum crisis and rising international interest rates in the early 1980s, resulting in the government introducing some liberalisation of the political system. Fearing a development similar to the one that befell the Argentine junta, whereby they had a sudden and humiliating fall from grace followed by tribunals, the Brazilian leaders sought a negotiated path to democracy.

Turning Away From the Bomb

With both military regimes out of power, civilian leaders both in Brasilia and Buenos Aires began gradually moving away from their nuclear aspirations, aspirations which were never fully about the bomb but rather about a general capacity to obtain one later along with a specific goal of having significant nuclear technological capabilities. In 1988, the Brazilian Congress adopted a new constitution (the country’s seventh), in which Article 21 Section XXIII Subsection A explicitly stated that “all nuclear activity within the national territory shall only be admitted for peaceful purposes and subject to approval by the National Congress.” As a result, a nuclear weapons programme had become unconstitutional.

At first, the two countries sought to improve relations by addressing other issues, like the economy, which they did by signing the Argentine-Brazilian Integration Act. Such steps helped create the necessary environment for eventual joint efforts to move away from a nuclear rivalry, a move that was largely accomplished by the two countries without significant third-party involvement. In 1990, the Brazilian president signalled the programme’s end by throwing two shovels into the test site, thereby burying it. In 1991, the two countries signed a bilateral agreement whereby both promised that their respective nuclear ambitions would be limited to peaceful purposes and would be ensured through the Common System of Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials, which was to be managed by the Brazilian-Argentine Agency for Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials. This was followed by the 1991 Quadripartite Agreement, which helped harmonise the works of the binational agency and the IAEA. In March 1993, the Argentine Senate finally ratified the Treaty of Tlatelolco. Brazil had signed the treaty in 1967 and ratified it in 1968 albeit with a reservation, a reservation that was withdrawn in 1994. In 1998, Brazil signed the NPT. Argentina went beyond just ending their nuclear weapons ambitions. Already dogged by years of American pressure (both directly and on third parties, in part due to concerns from Washington that the Cóndor II missiles were being available to some Middle Eastern states) dismantled its missile programme and joined the Missile Technology Control Regime in 1993.

The irony of the Argentine-Brazilian nuclear rivalry is that neither country fundamentally wanted nuclear weapons but both believed that the other’s programme posed a threat and that the only way to counter was by having their own, which in reality merely intensified the mutual threat. Rather, what both actually desired was security along with prestige even though the two had not been at war since 1828. Only once both countries began taking active measures to reassure the other through confidence-building measures were both able to gain the security that they desperately sought after.