Let’s try a thought experiment. Imagine for a moment that Argentina, Cyprus, and Spain conspired and simultaneously attacked and seized the Falkland Islands (or las Malvinas, if you are so inclined), the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia on the island of Cyprus, and the British Overseas Territory and city of Gibraltar.

In the case of the latter two London would presumably invoke Article 5 of the NATO treaty, which states “that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all.” However the involvement either directly or indirectly of existing NATO members would complicate matters and potentially result in the transatlantic military alliance not taking a firm position and even becoming paralysed. After all, Greece and Turkey, both of which were NATO members, fought a war in Cyprus without the military alliance getting involved.

As for the Falkands, unlike in 1982, the British military lacks the resources to deploy and retake the islands. Ultimately, it would depend on the United States’ inclination to get involved (or not). However, it is possible that Washington would see the three issues as being inconsequential for its own national interests, viewing them as unnecessary distractions given that the change in territorial ownership does not fundamentally impact the global balance of power.

If so, Britain would be left to its own devices.

The real question is not “what should the UK do?” but rather “so what?” The loss of the territories may prove to be somewhat humiliating and the fate of citizens would be a complicated, though not an insurmountable, challenge. However, is Britain any less safe? In fact, is it possible for an island (and a quarter) surrounded by friendly neighbours to be any safer?

Instead of obsessing over the number of tanks, the deployability of an aircraft carrier, or the stationing of troops in the Baltic states, perhaps British policymakers should take a step back and realise that a demilitarised United Kingdom is a viable albeit ignored option.

Freeriding vs Realism

The classic argument against not increasing military expenditure is that it results in a country unfairly freeriding on others. This line of attack has been deployed against the United Kingdom’s insular neighbour, Ireland. Eoin Drea, senior research officer at the Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies, put his criticism this way:

“And most depressingly of all, not even a direct Russian attack on the Baltic states, Finland or Poland may convince Ireland to lift a finger — or reach for its checkbook — to help defend Europe.”

Or, more bluntly:

“Two things are certain: Ukraine will keep fighting; Ireland will keep freeloading.”

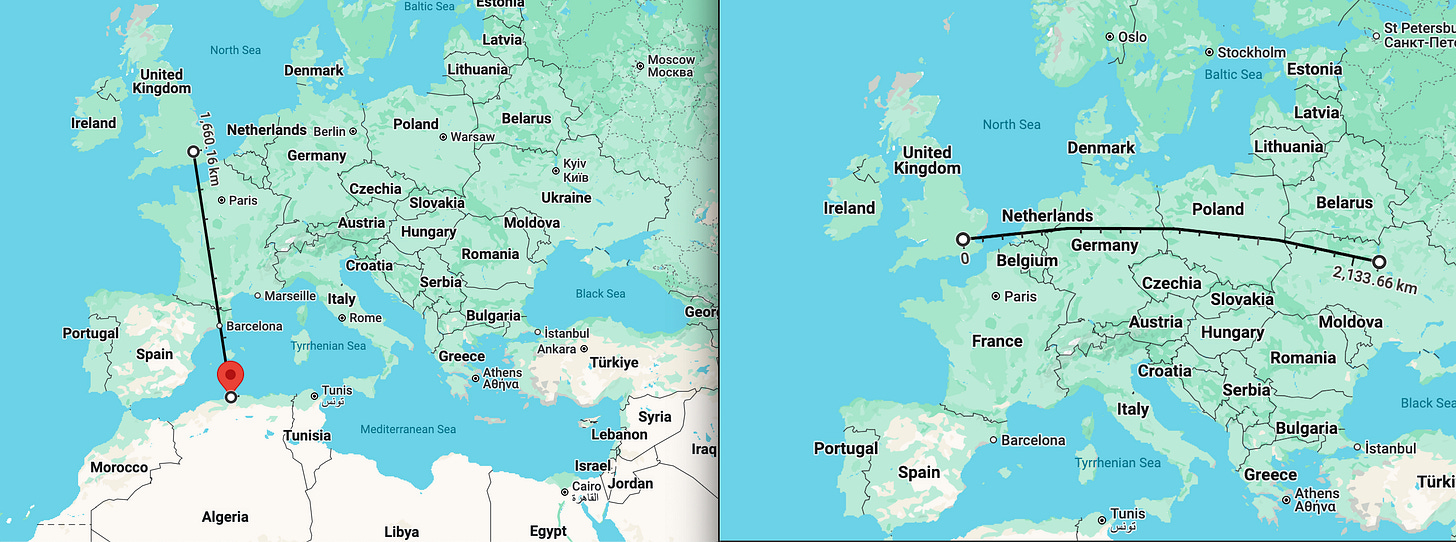

Yet this line of thinking assumes that Ireland has the same security interests as Ukraine. By this logic all countries on the same continent, no matter their location, ought to bind their fates with those in a radically different security environment. Dublin is approximately 2,500 kilometres from Kiev. By contrast the Irish capital is roughly 2,000 kilometres from Algiers but few would argue that Ireland is somehow morally obligated to pursue mutual defence obligations with Algeria despite the fact that Algeria acts as a buffer between Europe and the infernal fighting that has gripped neighbouring Libya, Niger, and Mali (not to mention many others not far beyond).

At its core, the same logic applies to the United Kingdom. In fact, the distance between London and Algiers is ca. 1,660 kilometres compared to roughly 2,130 kilometres between London and Kiev. A country can only be reasonably accused of freeloading if it is itself facing the same threat. However, if not threatened, then it is not freeloading. The Brits that are most at risk from the Russian military are not the civilians in the United Kingdom but those deployed as soldiers close to Russia’s borders. Seeking to combat alleged freeloading by exposing oneself to greater dangers may be morally self-comforting but does little for security.

Avoiding Unnecessary Embarrassment

Lacking the ability to deploy significant forces beyond its shore, the United Kingdom has repeatedly resorted to serving as a junior partner to the United States. The Chilcot Inquiry, which examined British involvement in the Iraq War, was damning in its assessment of the British role during the lead up to the war, the invasion, and the occupation itself. In the case of security sector reform, for example, “The UK was unable to influence the US or engage it in a way that produced an Iraq‑wide approach” while “The UK’s ability to influence the CPA [Coalition Provision Authority*] decision on the scope of the policy was limited and informal.”

In a bid to compensate for its declining role in Europe as a result of Brexit, the former Conservative government announced that it would send an aircraft carrier to the South China Sea to accompany the United States. What was the reaction from Washington? Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin stated that “If for example, we [the United States] focus a bit more here [in Asia], are there areas that the UK can be more helpful in other parts of the world [sic].” In other words, the UK ought to stop pretending to be an Asian power and focus more on Europe. So much for the special relationship. As other observers have correctly noted, “Global Britain” is nothing more than a slogan

During the Iraq War, British forces were tasked with securing the southern city of Basra, a mission that ended in a debacle. American graffiti in a portable toilet from this era, as observed by a member of the US Marine Corps, summarises the low regard that the British military endeavour was held in:

Q: How many Brits does it take to clear Basrah?

A: None. They couldn’t hold it so they sent the Marines.

Top a that morning chaps!

Meanwhile, in a bid to prove their nuclear, maritime, and global relevance, the United Kingdom committed itself to a nuclear-powered submarine coalition with the United States and Australia as part of a united anti-China front termed Aukus. Former Australian prime minister Paul Keating criticised the pact, calling it the “worst deal in all history” while deriding the UK for “looking around for suckers” to create “global Britain… after that fool [Boris] Johnson destroyed their place in Europe.” While the Australian government has remained committed to Aukus, regional powers Malaysia and Indonesia pushed back against it as well. In doing so, the United Kingdom has contributed to the erosion of non-proliferation efforts.

By wanting to punch above its weight, the United Kingdom is repeatedly putting itself in awkward positions that risk spinning out of control. In late 2023 Venezuelan-Guyanese relations worsened when Caracas asserted its territorial claim to Essequibo, a region widely recognised as belonging to Guyana. In response, London announced the deployment to South America of HMS Trent, a vessel that according to the BBC “is mainly used for tackling piracy and smuggling, protecting fisheries, counterterrorism, providing humanitarian aid, and search and rescue operations.” While the situation did not escalate into a war, the British deployment did not deter Venezuela from conducting military drills. But more fundamentally, does sending a ship with a crew of 65 seriously alter the balance of power in a largely terrestrial dispute? Or is it more likely to ensnare the UK into a faraway conflict with little to no strategic significance where it would play a marginal role at best?

Ultimately, aspiring to an unrealistic goal will either result in marginal benefits for Britain or risk leading the country into embarrassing entanglements in which it will have to be bailed out by its Anglo-Saxon big brother across the Atlantic if it is to save face.

Unilateral Nuclear Disarmament

Lord Richards, former head of the defence staff, bemoaned that the UK was essentially a “Belgium with nukes.” Meant as a criticism of the overall decline in conventional capabilities, it does unintentionally raise another question: should Belgium have nukes? After all, if having Belgian-level military strength is a bad thing, does it stand to reason that the Belgians should acquire nuclear weapons? Of course, that would not be considered a serious proposal (even though Belgium is wealthier than the United Kingdom on a per capita basis). So that leads to a second question: is Belgium militarily secure? The answer appears to be an obvious yes, being (like the United Kingdom) completely surrounded by friendly nations. So if Belgium is safe without nukes, it stands to reason that another “Belgium without nukes” could achieve at least comparable security that is no worse than the status quo. Despite this—and preceding the Russo-Ukrainian conflict and the resulting worsening state of Russia-West relations—then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced in March 2021 that his country would increase its nuclear stockpile by more than 40%.

An argument in favour of maintaining a nuclear arsenal is that it validates Britain’s outsized global role. One manifestation of this has been the UK’s permanent seat in the United Nations Security Council where it wields veto power. If one assumes that only great nuclear powers can justify their place on the Council (even though only one of the five had nukes at the time of its formation), the natural follow-up question would be: what is the consequence of the UK losing its seat? Strikingly, the answer would be either nothing if not even a net positive, depending on one’s perspective. In terms of actual votes, the UK has not unilaterally vetoed a resolution since 1972 (on the disputed British colony of Rhodesia). So in that sense, all votes since then (but also preceding ones excluding Rhodesian-related ones) would have had the same outcome. A more optimistic view on a British departure from the Security Council (perhaps even giving its seat to India) would be that it actually opens the United Kingdom up to voting in a manner that is not constrained to aligning—i.e. appeasing—the United States constantly.

On closer scrutiny, the nuclear-Security Council argument falls apart. While India, as an aspiring permanent member, has a nuclear weapons arsenal, many others do not. Brazil, Germany, Japan, and Nigeria all seek to sit at the decision table without relying on atomic bombs.

Fit for What Purpose?

In the absence of a direct threat to the British mainland and an increasingly marginal role internationally, what is the British military actually for? For some politicians, the answer is seemingly “everything.” Recent British governments have used the armed forces as a type of Swiss army knife to deal with a host of different challenges that have little to no relationship to traditional military duties. Whether it is snow storms or the Olympics, the military has been used as a bandage. A particular notable example was when 600 armed forces personnel were called on to fill in for striking Border Force employees in 2022. As the Guardian reported on it:

“They were given five days of training and brought in to take people’s passports and check them against the “warnings index [WI]” – a Home Office watchlist database with information such as previous immigration history and matters of national security.

Border Force guards are usually given a minimum of three weeks of training before they interact with the public. After that they are given a mentor to work alongside for up to a month to ensure they can work solo on a passport desk.”

According to a press release by the Royal Air Force (RAF), “[m]ore than 200 RAF personnel were part of the military contingent who covered the duties of UK Border Force staff and ambulance drivers during strikes in late December [2022],” which included people as young as 17.

Instead of spending money on the military to serve as inter-departmental temp workers, Westminster would be better of using its £54.2 billion (2023/2024) budget to finance the various government departments adequately. Resorting to crisis management by relying on soldiers being jacks of all trades but masters of none is also a cost-inefficient endeavour.

Furthermore, the military already faces a recruitment crisis. As noted in an earlier article:

“… for most British people, the country is not a particularly rich one, especially by Western European standards. While the unemployment rate is officially just above 4% there are approximately 11 million economically inactive working-age people in a country of 69 million. Despite this, the UK still suffers from a recruitment crisis. In a twelve-month period in 2022-2023, 51% more people quit the armed forces than enlisted (16,140 leaving as opposed to 10,680 signing up). While some news outlets and politicians have needlessly framed this as meaning the that the army is the smallest it has been since the Napoleonic wars—is London still ruling Canada and India?—it does suggest that even poorer developed countries are hard pressed to find enough soldiers.”

By maintaining its global military ambitions—ranging from the South Atlantic to the Baltics to the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean—the British government is committing itself to a military role it simply cannot sustain. The least it can do is scale back its goals, potentially all the way back.

Concluding Thoughts

The transition towards a demilitarised state is not cost-free; new jobs for demobilised troops and those formerly employed in military-industrial productions will need to be found. Nevertheless, with no nearby threats, being a global military influence remains a naive (if not even a delusional) aspiration. The British government should cooly and rationally assess its own immediate security needs, not seek to act as a significant military power that can provide security for dozens of other countries.

* The Coalition Provisional Authority was the initial governing regime of post-invasion Iraq, which was headed by American official L. Paul Bremer who was widely seen as a de facto viceroy.

This point connect with the delirant plan of create an EU army. First: there is no European State, and the armies are instruments of the State. Second: as you say, ¿will an Estonian be interested in going to Ceuta to fight against Morocco for the interests of Spain¿ ¿and will an Spanish find any reason to go to Ukraine? There is not a Political Unity with the same interests; and without that, an army is crazy. Third: ¿will these be profit by militar industries of Europe or will be bought to USA industries? Is more: there a plurality of military industries in Europe, and each country will try to be the one that produces military incomes (France and Spain, for example, will fight for get contracts).

However, the UE administration and leaders need to keep their charges. Also, they need to justify their job, and an enemy like the evil Russia is a good symbol. Also, they need to have a good image of itself (not all is maquiavlellism, there is real convincement and ideology also). Every institution, doesn't matter the size, tend to maintain and grow itself, independently of the accomplishment of it initial function. A lot of plural interests are created in a decentralised network (that's why affects media, companies, different regions of Europe and inside the countries, status of micro-groups like students, enterpreneurs, analysts,...). This is a sociological law.

The same recommendation that you give to the British it is applicable here (even more).