This is the third and final part of this series on the Ethiopian Civil War. The first part can be found here and the second part here.

The Eritrean Guerrillas

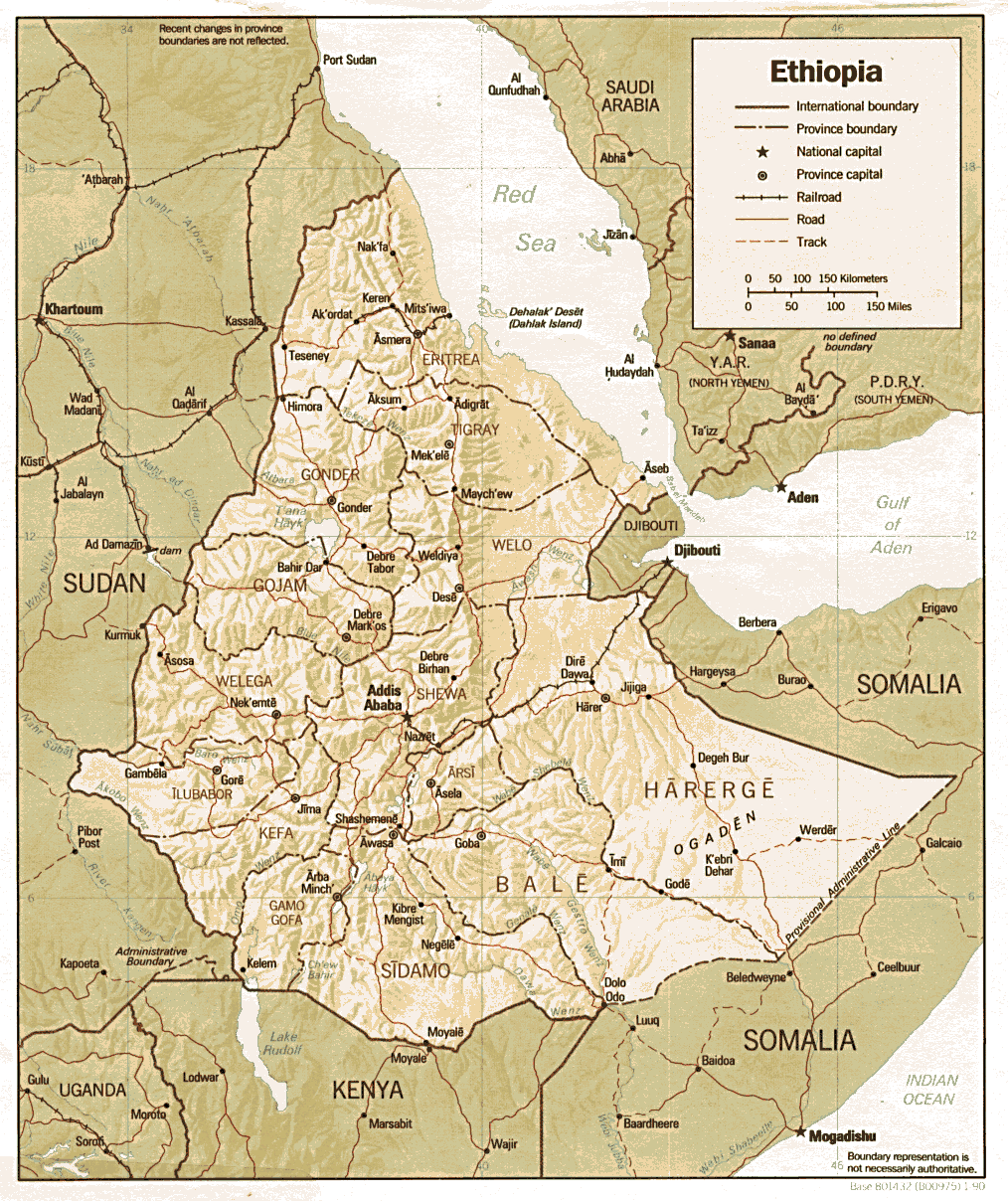

The most significant rebel movement during the Ethiopian Civil War was in the northern province of Eritrea. The conflict began in 1961 when rebels belonging to the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) under the command of Hamid Idris Awate launched the first attack on Ethiopian forces. The fighters had initially organised abroad, primarily in Arab countries such as Egypt and then later also Sudan and Algeria, even modelling itself in part on the latter’s successful National Liberation Front. To some extent, their efforts were influenced by contemporaneous pan-Arab movements, which was further reinforced by additional support from the governments of Iraq and Syria. For the Ethiopian government, Eritrea was seen as vital since it was Ethiopia’s access to the sea, without which it would become landlocked once again.

Albeit a secular movement, the ELF was noted for its predominantly Muslim membership. This caused some uneasiness with some Christian members, a concern that continued to grow as the ELF’s reliance and interaction with Arab governments increased. Ultimately the Eritrean movement split into two, with the breakaway Eritrean People’s Liberation Front emerging, though neither side was by any means homogeneous with both having significant numbers of highland Christians and lowland Muslims from various ethnic groups.

The Eritrean War of Independence, which predates and was subsumed as part of the wider Ethiopian Civil War, experienced its own factional civil war between the ELF and EPLF. The presence of competing rebel forces reduces the likelihood of a rebel victory even if they share a common enemy (i.e. the government). In a bid for hegemony within the Eritrean rebel movement, the two sides came to clash, resulting in the EPLF displacing the ELF as the predominant guerrilla force.

The EPLF was noted for its sophisticated and effective organisation. While much of their armaments and equipment were captured from government forces or smuggled across the border via the Sudanese border town of Kassala, the EPLF also established small-scale workshops that produced uniforms and spare parts for weapons as well as provided medical care and education in rebel-controlled areas. In addition, it stood out for having a large female contingent; roughly 30% of their fighters were female.

From Bad to Worse: The Famine

As the saying goes, “it’s never so bad that it can’t get worse.” In Ethiopia’s case, this was certainly the case in 1983-1985 when the country was hit with a famine. Famines were by no means unusual in Ethiopia, they tended to occur approximately every decade and were caused by everything from drought to locust invasions to animal-borne diseases.

Despite his pledges of modernisation, Emperor Haile Selassie had left the country behind with poor infrastructure, making relief efforts much harder for socialist Ethiopia, resulting in heavy reliance on aid being delivered by air, a far more expensive endeavour. Some of the problems were also self-inflicted. The intense civil war also led to the widespread use of landmines, leaving otherwise arable land out of use. In addition, the government pursued a policy of resettlement and villagization. Ostensibly, it was intended to help people move to new areas that were not famine-stricken as well as bring together individual homesteads in order to improve access to water, education, and medical care, which could be more easily done with increased population density. According to Ethiopia’s socialist-era leader Mengistu Haile Mariam, “Collecting the farmers into villages will enable them to promote social production in a short time. It will also change a farmer’s life, his thinking, and will therefore open a new chapter in the establishment of a modern society in the rural areas and help bring about socialism.” While some of those motives were sincere, it was also heavily guided by counter-insurgency objectives, such as weakening rural support for the rebels by cutting them off from one another.

Villagers that previously practised a mixture of farming and herding were forced to abandon the latter. Offensives that coincided with planting seasons also harmed the agricultural sector. In addition, the restriction on movements internally and greater demands by the government in order to sustain cities and the military further contributed to turning a drought into a massive famine. The government prioritised heavily state-owned or controlled coffee farms, which were seen as an essential economic lifeline since coffee exports was the country’s leading export and a major source for hard currency. The significant need for hard currency also impacted Ethiopia’s relationship with East Germany. East Germany was experiencing a coffee shortage so had offered Ethiopia military support in exchange for coffee. During a visit to East Germany in October 1977, Mengistu said ‘thanks to the GDR’s [German Democratic Republic, i.e. East Germany’s] aid, it was possible to equip and feed 100,000 men of the people’s militia.’ In this way, the GDR played a significant role in the revolutionary development of Ethiopia. However, within less than a year the agreement broke down. Even as East Germany offered more aid, infrastructure projects, agricultural machinery and training, which politburo member Werner Lamberz argued would be more effective than pure reliance on armed strength, Ethiopia ended the agreement, demanding hard currency, which in turn resulted in growing dissatisfaction in East Germany towards its government as a result of the ongoing coffee shortage.

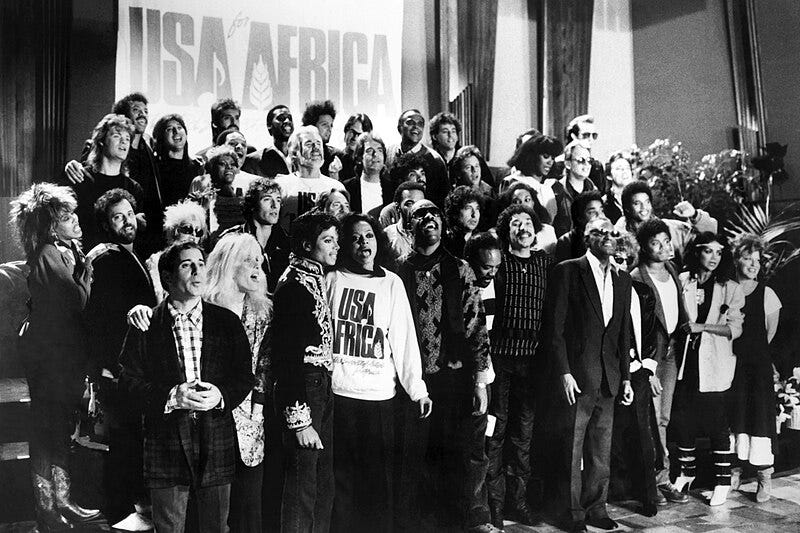

The famine, which one BBC journalist described as “biblical,” caught worldwide attention. Countries on both sides of the Iron Curtain sent aid as images of starving children permeated the world press. It also led to some of the most high-profile musical examples of humanitarian relief efforts. After watching a news report on the famine, the artist Bob Geldof helped bring together a group of artists who, under the name “Band-Aid,” performed the song “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” The song was an immense success and the following summer Geldof organised “Live Aid,” a benefit concert that occurred simultaneously in London and Philadelphia. The concert brought together some of the biggest names in music, such as Queen, Elton John, U2, the Beach Boys, Run DMC, and others. Geldof was not the only one to lead such an effort. Following the success of “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” Harry Belafornte sought to replicate its achievements, first by recruiting Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie as songwriters and Quincy Jones as a producer. The result was “We Are the World,” which also featured artists like Bruce Springsteen, Cindy Lauper, Stevie Wonder, and many more.

The British government, meanwhile, was rather ambivalent towards humanitarian efforts to Ethiopia. On the one hand, public (and global) reaction to the famine meant that the government was inclined to provide aid, which it did. On the other hand, Britain’s right-wing prime minister Margaret Thatcher was worried that by providing aid the government was indirectly propping up the Derg. This led to internal discussions on whether or not to seek to undermine (and thereby potentially assist with the overthrow) of the Derg.

The Final Years

The Soviet Union was the Ethiopian government’s biggest ally, providing massive support that turned Ethiopia to one of Africa’s biggest military powers. However, the two were not always aligned. In particular, the Soviet government sought to reconcile the Derg and rebels, many of whom already adhered to one form of socialism or another, including Marxism-Leninism as well as varieties like Maoism and Albanian-inspired Hoxhaism.

Mikhail Gorbachev’s rise to power in Moscow reduced crucial Soviet backing for Addis Ababa. Gorbachev initiated the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, the removal of Soviet troops from Eastern Europe, as well as faced American pressure to cut back support for governments across the world as part of improving East-West relations. For the People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (which had been established following the adoption of the 1987 constitution that sought to transition the country to civilian rule under the Workers’ Party of Ethiopia—founded in 1984—despite many military officials, including Mengistu, retaining leading roles), the timing could not have been worse. Not only were the rebels on the advance and the Ethiopian military heavily exhausted by having to fight a multi-front counterinsurgency that spanned from flat plains to mountains, it would also coincide with an internal challenge to the ruling power.

As casualties mounted, exhaustion set in, and no end in sight, some officers began to conspire against Col. Mengistu. During the latter’s four day state visit to East Germany in May 1989, officers launched a coup. Within days, government loyalists successfully crushed the putschists, with several of the plotters either killed or later executed. While the government was not overthrown, its days were still numbered.

The last few years of the conflict consisted of a string of rebel victories. At the Battle of Afabet—possibly the largest battle in Africa since WWII and compared by some to Dien Bien Phu—EPLF forces killed, wounded, captured or dispersed approximately 15,000 government troops, as well capturing three Soviet officers. The defeat was so significant that for the first time ever Mengistu acknowledged publicly what the whole world already knew, that the country was in a state of war. In Tigray, four divisions were defeated at the Battle of Shire and 12,000 government forces surrendered in February 1989 to the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). In 1990, the vital port city of Massawa fell to the rebels.

Simultaneously, various rebel groups began coordinating. EPLF and TPLF in particular collaborated. In addition, the latter also helped create a pan-Ethiopian rebel alliance known as the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). Combined with the end of Soviet support and continued exhaustion, the People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia was teetering on the brink of collapse.

In the spring of 1991, as EPLF rebels took the Eritrean capital of Asmara and EPRDF forces advanced closer to Addis Ababa, Mengistu Haile Mariam fled the country, initially travelling to neighbouring Kenya before finally settling in Zimbabwe. In Zimbabwe, Mengistu found sympathy from the authorities, who rewarded the former Ethiopian leader for his support for Robert Mugabe’s rebel movement during the waning years of white minority rule in the southern African pariah state of Rhodesia.

In Addis Ababa, the EPRDF established a transitional government that lasted until 1995, when the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia was established. The TPLF would go on to dominate Ethiopian politics until 2018. Despite having fought for thirty years, Eritrean guerrillas—now in control over the entire province—agreed to wait two years before holding an independence referendum, which was finally held in 1993 resulting in over 99% of the population voting in favour of independence. Following its victory, the EPLF became the People's Front for Democracy and Justice. Despite both countries being ruled by former allies, Eritrea and Ethiopia would go to war again in 1998-2000. Though an agreement was nominally reached in Algiers in 2000, border tensions remained and it was not till 2018 that both sides declared peace. Meanwhile, the TPLF fell out of power and clashed with its own government as well as neighbouring Eritrea, resulting in the Tigray War between 2020 and 2022.

Suggested readings:

https://newleftreview.org/issues/i67/articles/fred-halliday-the-fighting-in-eritrea.pdf

https://manaramagazine.org/2020/12/the-dilemma-for-rebel-leaders/

https://www.hrw.org/reports/pdfs/e/ethiopia/ethiopia.919/d3villag.pdf

https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/ethiopian-civil-war-failure-counterinsurgency

https://www.hrw.org/reports/pdfs/e/ethiopia/ethiopia.919/d4afabet.pdf

https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/papers/2019/P7574.pdf